The First Victoria Hospital 1886-1896

Money had been collected to establish a hospital at each terminus of the railway line, but the line always moved on before it could be built.

In May 1887, Mrs. Francis, wife of the Police Magistrate, called a public meeting of ladies and suggested that Queen Victoria’s jubilee in June should be celebrated by establishment of Victoria Cottage Hospital. She told them,

As the men have failed in their attempts, it is now the women’s turn.

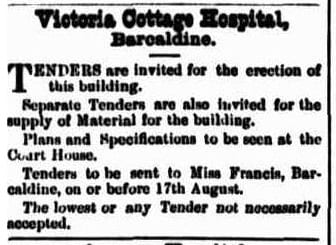

With the help of her daughter and a hard working committee, Mrs. Francis carried her proposal to immediate success. Jubilee week saw a series of functions from which all proceeds were donated to a hospital. So generous was the response that by August a site was chosen and in September a tender of £353.11.10 from Meacham and Leyland was accepted for construction. James Meacham and James Leyland were carpenters who founded a business at Pine Hill in October 1884 and moved via Jericho to Barcaldine with the railway.

When Victoria Hospital (the word ‘cottage’ was dropped) opened in the first week of March 1888, the ladies handed over administration to a committee of men.

But one of the first documented pieces of evidence of women’s leadership is available to us in the plaque erected at the Queen Victoria Hospital when it was opened.

THE UNDERMENTIONED LADIES WHO, IN THE JUBILEE YEAR OF QUEEN VICTORIA’S REIGN IN THE SPIRIT OF SYMPATHY AND HUMAN SUFFERING WHICH IS THE GLORY OF THEIR SEX, FIRST THOUGHT OF ESTABLISHING THIS INSTITUTION, AND IN THE FACE OF OBSTACLES WHICH WOULD HAVE DETERRED ALL BUT THE MOST RESOLUTE, CARRIED ON THEIR OWN UNAIDED EFFORTS, THE PROJECT TO A SPEEDY AND SUCCESSFUL ISSUE.

THIS HUMBLE TRIBUTE IS GRATEFULLY AND RESPECTFULLY INSERTED BY THE HOSPITAL COMMITTEE.

MRS. A. M. FRANCIS

MRS W. H. CAMPBELL MRS A. J. A. MOODY MRS J. HYLAND MRS W. H. CAMPBELL MRS A. PARNELL MRS E. A. PEEL MRS. R. MATTHEWS MRS E. C. SHAW MRS R. SUMMER MISS FRANCIS MISS SAVAGE

Parnell, Lloyd-Jones, Cronin, Moody, Savage, Shakspeare, Hyland, Campbell, McDermott, Peel and Ellis were the first committee members with Mr Francis in the chair. Representatives of the district’s country properties became trustees (E. King, Coreena; G. Fairbairn, Mimerah; R. Hopkins, Wellshot; J. Niall, Delta; R. Brown, Saltern Creek). F. R. Murphy, MLA accepted the position of president and was able to arrange a government grant of £1,000 for extensions to the building. Vice presidents were J. Holdsworth, Traffic Manager of the railway, and J. Petersen, manager of Wright Heaton, Forwarding Agents.

The Early Doctors

Dr. (George) Owen Willis, who had been practising privately, was appointed Medical Superintendent for a trial period of six months. Some exception was taken to the appointment, for Dr. Willis was a handsome distinguished man with a weakness for women and a penchant for performing ‘feats of surgery’. The first patient admitted to Victoria Hospital suffered amputation of a finger.

Dr. Willis was supported by William Campbell, who described these surgical feats in detail in the Western Champion and attracted custom from as far away as Winton. The doctor was assisted at his operations by any woman strong enough to stand the sight of blood and the agonised screams of patients. Alcohol was the main anaesthetic and trained nurses were unknown.

Dr. Willis ran a chemist-cum-fancy goods emporium in addition to his practice and indulged in an affair with the wife of a committee member. Not surprisingly, he was replaced at the end of his trial, his failure explained grandiloquently in the Champion as being because:

he was not yet acclimatised to the rarified atmosphere surrounding our colonial aristocracy.

Dr. Paul, appointed in his place, resigned almost at once, unable to ‘stand the parochial wrangling of this outlandish spot’ and Dr. Cumming took charge. The town supported two doctors, one at the hospital and another supported by contributions to Friendly Societies (Foresters, Hibernians, Oddfellows, Freemasons).

Sometimes the duties of the doctors overlapped and their lives were complicated by a chemist, Oscar Bancke, who set himself up as a doctor. Bancke, from Denmark, arrived in Barcaldine in the winter of 1887 and flourished for years in the town, switching prescription, persuading patients to try his treatments instead of the doctors’ and sending off his ‘mistakes’ to die in the hospital. He profited so well that by the time he left to try his fortune in Longreach, he was able to sell up two hotels and a number of other buildings as well as his practice as a chemist. After his death in December 1902, the Champion reported with customary forthrightness that it could be attributed to immoderate use of chloral and narcotics.

Chronic ill health kept the small hospital busy. Typhoid was endemic and to stop pollution from back yard hole-in-the-ground toilets, the Divisional Board installed in 1894. The waste was dumped into an open hole about two miles from town until an epidemic of scarlet fever brought a decision to have it buried and to force the use of correct pans instead of kerosene tins.

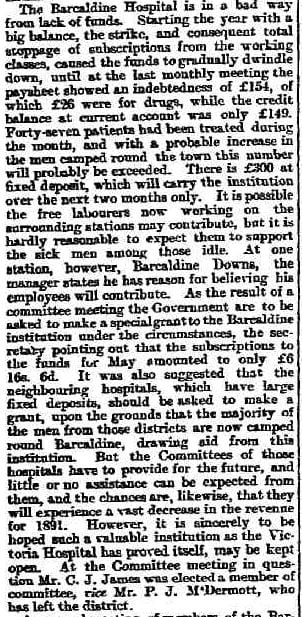

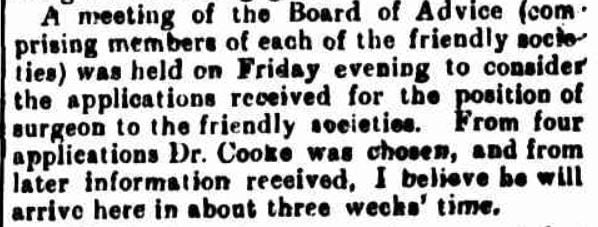

During the shearers’ strike the hospital was unable to cope and had to turn away patients from the camps thus incurring the wrath of the unions whose members contributed to its upkeep by a levy on union tickets.

The second medical superintendent, Dr. Cumming, resigned in 1892 after a public feud with Dr. Hewer of Aramac because he discharged a patient who died later in Aramac Hospital. From 33 applicants, Dr. Francis was chosen to replace him. He was the son of police magistrate, A. Francis, whose wife had founded the hospital, and he moved into Craigneish, the family’s old home. The young doctor accepted the position because his wife suffered from tuberculosis and he hoped the dry climate might help her. His memoirs, Then and Now, have interesting anecdotes of Barcaldine life during the two years he spent there although his wife lived only a few months.

Dr. Symes from Blackall was the next superintendent and his report for 1894 state that 107 males and 13 females were treated at the hospital and 303 outpatients. Obviously women were seldom admitted to the rugged institution. No listing was given for children but mortality of infants was high, with periodic outbreaks of infectious diseased for which there were not miracle drugs and no vaccines. In October 1894 over 40 babies were ill with three deaths reported in one week.

Aborigines were sometimes treated at the hospital but its financial problems did not allow for much charity. The following case conundrum for the Council illustrates the point:

The letter referring to the case of the aboriginal " Tommy" caused some discussion. It was stated that when the aboriginals were despatched from Barcaldine a few months ago "Tommy,'' who was sick, was left on the reserve, a couple of blacks being retained to look after him. However, "Tommy" got no better, and was evidently a nuisance to the police. By the Sergeant's orders, therefore, the black was taken to the hospital, and dumped down somewhere in the precincts of the institution. A tent was found the sick man, and Dr. Cook attended him, but the old fellow conveniently died, after a fortnight's physicing, and to save cemetery fees was carted away into the bush and buried by Messrs. Meacham & Leyland, the contractors for burials.-Dr. Cook was very severe condemnatory of the conduct of the police : the police had everything to do in the matter and should have left the man to be taken care of by his fellows. If he died-and the man was moribund when he was brought to the hospital-the blacks would have seen to the burial according to their customs.-Mr. FERGUSON thought it a disgrace for anyone to allow a patient taken from the hospital to be buried in the bush, be he either black or white.-Mr. PARK said the police had made a " bloomer," and wanted to shove the responsibility of burial on to the hospital committee. -Messrs. PEUT and JAMES said that the hospital committee would undoubtedly have to foot the bill. The hospital was open to any one, and if 1 man died on the premises the institution would have to bury him if no one guaranteed payment. -Mr. PARK said the Home Secretary had heard only the police side of the affair; he thought the hospital committee should have something to say; the committee should resist paying the £4 as long as possible.- Mr. FOTHERGILL thought a great injustice to the hospital was attempted to be perpetrated. Eventually, on the motion of Mr. PARK, seconded by Mr. O'BRIEN, it was decided to acknowledge the letter from the Police Department, and to ask the Sergt. of Police to again write the Home Secretary, through the Police Department, pointing out the circumstances of the case from the hospital committee's point of view.

Western Champion 5 October 1902

1896 Fire

On 29 January 1896 the whole building was destroyed by fire. The blaze began in a detached kitchen just before dawn so there was time to rescue all patients and some equipment. It was destroyed by fire because there was no water pressure or fire fighting equipment.

Afterwards the disused brewery, then owned by Peter Vesper, was fitted out as a temporary hospital. Wards were set up in the basement and upper story while Dr. Symes examined patients among cranks and fly wheels of the engine room for almost a year.

A most disastrous fire occurred this morning about five o’clock at the Victoria Hospital, ending in the complete destruction of the building. The fire, which broke out in the kitchen, was caused by a burning piece of wood falling from the stove, and setting fire to the flooring. The patients were all safely removed to the Brewery, which was speedily made available for the purpose. A large portion of the bedding and furniture was saved, but the wardsman and his wife lost all their personal belongings and £18 in notes. The servant girl was equally unfortunate, having lost all her clothing and £15. The building and furniture are insured for £1500. The Hospital Committee propose putting up at once temporary accommodation for the patients, until the new buildings are completed, for which plans and specifications will be at once prepared, and no time will be lost in beginning the work. It is possible that the Committee may select a site for the new Hospital at a greater distance from the Woolscouring and Boiling-down Works than the present one, as the fumes from these works must be very hurtful to the patients (Capricornian 1 February 1896).

Second Victoria Hospital 1896-1953

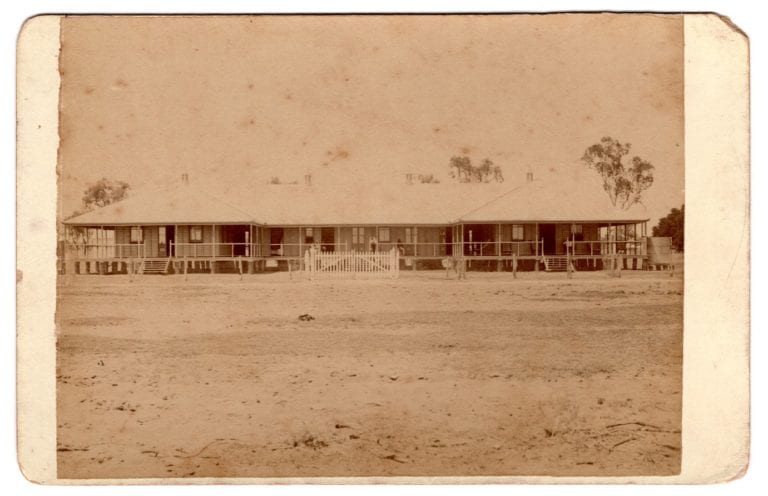

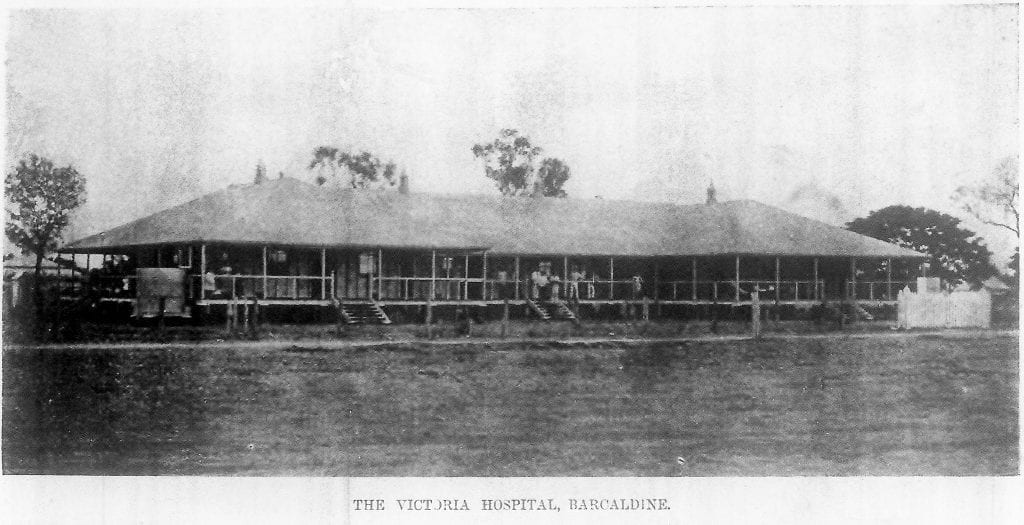

With funds from insurance, charitable donations and government subsidy, a new larger hospital opened in October 1896 with beds for 20 patients, wide verandahs, a good kitchen and other facilities. It was built by Meacham and Leyland for £1542.5.4.

Dr. Neilsen took charge, Dr. Symes having resigned in September after a scandal involving the wife of the wardsman.

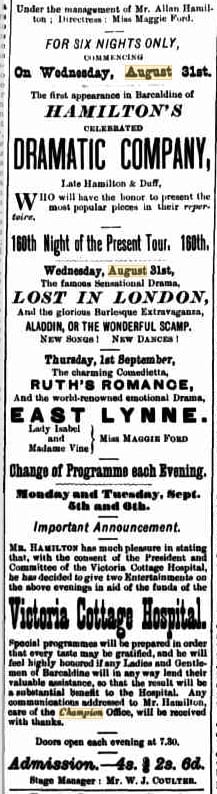

To build up funds for the hospital the committee installed slot machines called Automatic Medical Batteries in six hotels, the railway station and at the post office. They brought such good returns that the government withdrew its 2d for 1d subsidy on them but the committee circumvented that by giving all the money to one member who banked it as a donation, which did attract subsidy.

Dr. Neilsen resigned in April 1898 after being sued by Wah Sung for a dishonoured promissory note, and an enquiry into the remarkably high alcohol order at the hospital. Dr. Lyons, the Lodge doctor, acted as locum until Dr. J. M. Cook was appointed in September 1898 and Victoria Hospital entered into a new era of respectability and service to the public. Gone were the scandals and drink-sodden operations of early years. Dr. Cook was a sound physician who avoided surgery except in emergency. He did not drink and because of chronic deafness shunned social life and absorbed himself in work. Until age and increasing deafness led to retirement in 1929, Dr. Cook served the ill and injured of Barcaldine with dedication.

Typhoid was endemic along the railway in the dry years. A gang working on a deviation at the Main Range sent 14 cases to Victoria Hospital in February 1898, taxing its finances and accommodation to the limit. Five children with diphtheria were nursed in tents in May 1899 and fear spread through the community in 1900 as bubonic plague caused 12 deaths in Rockhampton in June, including a child of a Barcaldine shearer. Fortunately the disease did not spread inland.

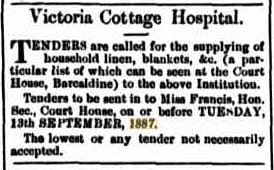

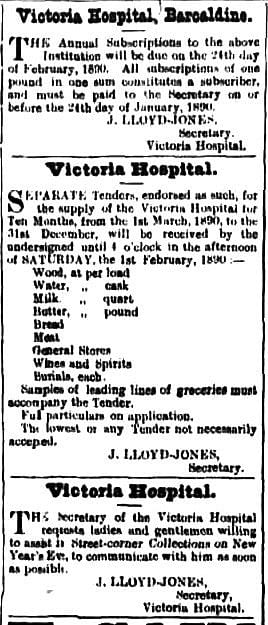

The Hospital committee sought government help to cope with rising costs and threatened drastic measures against outpatients who could afford to pay but ‘sponged on charity’. A. Moody, the Queensland National Bank manager who had been treasurer of Victoria Hospital from its inception, and had signed cheques worth £17,000 and steered the institution through three periods of ‘being without funds’ when he was transferred in 1901. In 1902, the committee lost its original secretary with the death of auctioneer and agent, J. Lloyd-Jones.

Influenza 1919

In 1919, on New Year’s Eve, ‘all the world and his wife’ went out onto Barcaldine streets to welcome in the new year – a year of peace and returning soldiers. Sadly, it proved another year of distress because the troops brought pneumonic influenza. Despite efforts to confine the illness to southern states – wearing of masks in city streets and a quarantine line at the Queensland border – the epidemic reached Central Queensland by the winter of 1919.

In May, representatives of Barcaldine Council (Fothergill, Parnell, Dyer, Fysh) met a hospital committee (McCullough, McBride, Park, Chambers and Dr. Cook) to plan for the emergency. Soon afterwards the first case, a railway guard, J. C. Bleney, was taken ill near Beta and brought to Victoria Hospital. By mid June inoculations given by Dr. Cook were proved useless. The supper room at the hall was inadequate and the main hall was put to use as an emergency hospital with Alice Leyland as nurse-in-charge. Normal like came to a standstill. Railway staff were ill, the telephone exchange shut down from 6 pm to 9 am, schools and places of public gathering closed and the Western Champion was printed with the aid of ‘camphor, sheep dip, Epsom Salts and tobacco’. Hundreds of people were confined to bed in hospital, in the hall, or in their own homes. Dr. Cook’s son, Dr. Cecil Cook, arrived from the south to assist his exhausted father. They were helped by C. Fysh (Shire Clerk), T. Graham (chemist) and E. O’Brien (businessman).

There were several deaths each week, including that of William Campbell, senior partner of the Western Champion. The Hon. William Campbell lived in Brisbane after becoming a Legislative Councillor in 1906 but regularly returned to Barcaldine. He was ill at his residence, Craignish, for a week but appeared to recover and handed in his leading article as usual on June 16, the evening before he died. Campbell was almost 73 and apart from his business and political careers, was an artist who displayed his work at the Brisbane Exhibition. His funeral in the dining hall at Craignish was attended by a large crowd despite the epidemic.

When its public support funds were diverted to the war effort, the Hospital was disadvantaged. It also lost donations from Alpha/Jericho area because a hospital opened at Alpha in 1913. The Health Department pressed for construction of an isolation ward but the committee could not finance it and in 1921 it was built by state funds. The local support did provide nurses’ quarters in 1911, electric light, fans and a new kitchen wing in 1918-19, a septic system in 1921, and in 1924 a maternity ward, the first in a western hospital.

Admissions to Victoria Hospital increased each year, and mortality decreased with improved standards of medical care. The surgeon’s annual report of 1905 listed 179 in-patients and 758 out-patients with 10 deaths for 1904.

In the 1925 report for the previous year the numbers were 289 in-patients and 953 out-patients with 5 deaths. There was an exception in 1919 with Dr. Cook’s poignant reference to ‘the most awful tragedy of the institution’ – seven deaths in one week from bushfires.

Victoria Hospital as a community controlled institution was a victim of the hard times in the 1920s. An operating theatre, planned from 1926, was opened by the Home Secretary, J. Stopford in April 1928, but its construction was a disappointment. There were unhygienic cracks in the plastered walls and no money for repair.

In May 1928, the president of the hospital committee, R. Park, called a meeting to seek ‘urgent assistance of the public’ because of the ‘precarious financial position’. Although contributors responded well, and a Commercial Travellers’ Day in October raised £300, some of the hospital’s independence had to be sacrificed.

With government assistance, came an enforced change of name.

The last meeting of Victoria Hospital Board was held on July 4, 1928. Thereinafter the institution was known as Barcaldine District Hospital and meetings were attended by two government appointed representatives – Spence and Meacham.

Text Source: Hoch, Isabel. 2008. Pages 32, 33, 39, 40, 47, 68, 69, 71, 77, 87