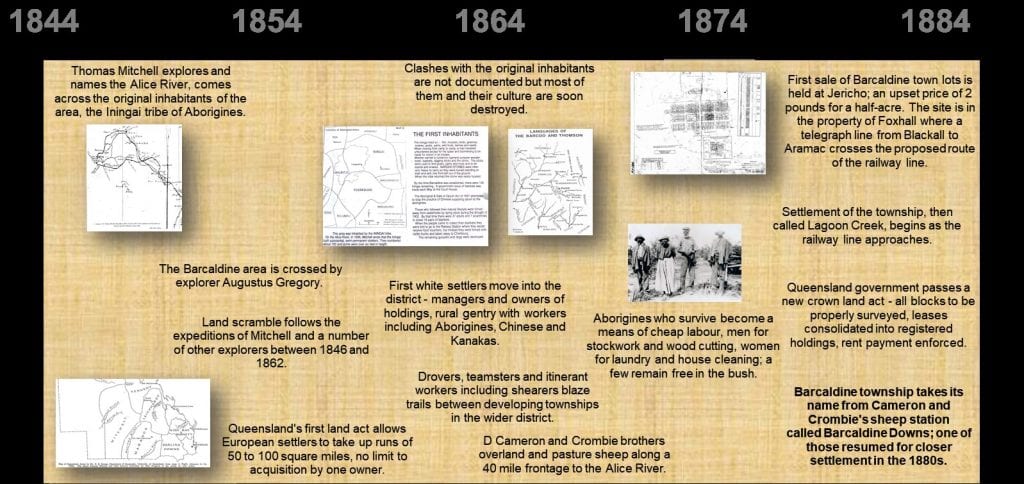

First White Men to Explore the Area

The first recorded white men to explore the Barcoo River were Sir Thomas Mitchell and two of his party.[i]

In September 1846, at the north-western extremity of his expedition into the interior of Tropical Australia, Mitchell reached the southern part of what became the Shire of Barcaldine. He was almost at the end of his endurance and his provisions but was so excited by country he described as

‘almost boundless plains . . . forming the finest region I had seen in Australia’

that he struggled on even after one of his pack horses had become too sore-backed to carry a load.

Mitchell came after winter rain and saw only the best the region could offer. He traversed the headwaters of the Barcoo, which he patriotically named the Victoria, in a loop that took him from near the present site of Blackall to beyond the river’s junction with the Alice and then back to where he had left his main party. He wrote:

‘this is no sandy bedded river like others, but has a bed of firm clay, with rich vegetation on the banks, a goodly continuous channel’.

He described rich herbage, told evidence of ‘impetuous floods’, wrote of pelicans, ducks and abundant wild life and of ‘grass shooting up green from old stalks’. Mitchell named it the Alice River.

Mitchell’s name was adopted for the pastoral district and for its famous grass.

First White Contact with Iningai People

At the time of Mitchell’s epic journey the area was inhabited by the Iningai tribe of Aborigines. On 21 September 1846 Mitchell came upon a group of their huts which he found to be of

‘more substantial construction . . . than usually set up by Aborigines of the south’.

The huts had a frame with lean-to roof, rafters laid upon that and covered with thin portions of bark-like tiles. He also saw shells of mussels the natives had eaten

‘like snow covering the ground’.

On September 25, a few miles west of the Alice, he came upon huts of a ‘very numerous tribe’ with fires still burning, well beaten paths and large permanent huts. He was anxious to avoid confrontation but was obliged to keep to the river and later that day encountered a big group disporting themselves in a lagoon and digging for mussels. His party were greeted by loud shrieks of women and children and by angry shouts of the men who called “Aya minya” taken to mean “What do you want?” Mitchell was, at all times, accompanied by a faithful black boy called Yuranigh, but the native was clearly as alarmed as his master and unable to understand the Iningai language. “You go on”, Yuranigh advised and Mitchell proceeded steadily forward ignoring the tribe.

‘Our position was anything but enviable’ he wrote, describing ‘an iron tomahawk with a long handle that glittered high in the hands of a chief’.

They were much relieved to be allowed to pass without attack and to hear the threatening cries grow fainter as they moved away. Five miles further on the men found the junction with a river 400 yards wide and turned back along the Barcoo to re-join the main party.[ii]

Further Exploration

Sir Thomas Mitchell returned to Sydney believing that the river he had found flowed to the Gulf of Carpentaria. In 1847 Edmund Kennedy who had been his second in command, was sent to find out if it did. Kennedy proved otherwise by following the Barcoo past its junction with the Thompson until it curved to the south west and became Coopers Creek, already discovered by Sturt. [iii]

In the years 1858 to 1862 three more expeditions passed through or near the district which later became Barcaldine Shire. A. C. Gregory, in search of Leichhardt, travelled the same route as Kennedy took as far as the Thompson, and then turned southward eventually arriving in Adelaide.

Three years later, on 25 August 1861, Frederick Walker, originator of the Native Police Force, left Rockhampton with a party of four men and seven native troopers. He crossed the Alice and Thompson Rivers and made his way to the Gulf of Carpentaria where he was instructed to rendezvous with William Landsborough who had been sent there by ship. In 1862 Landsborough travelled overland in a southerly direction across the Thompson, the Barcoo and the Warrego while Walker returned to Rockhampton via the Burdekin district.

Walker and Landsborough were officially in search of Burke and Wills but were believed to be ‘run hunting’ (finding good pasture) for squatter friends, a theory refuted by J. T. S. Bird who wrote

‘Such an opinion is libel on the face of it for . . . they never sold their information to capitalists’. [iv]

Fate of Iningai People

Whether they did so or not, a land scramble followed their expeditions and the white invasion spelled doom for the Iningai people. These tribes which had so impressed Sir Thomas Mitchell, inhabited a wide area of the Central West from the Dividing Range to the Thompson River, south along the Alice River and north to where Muttaburra developed.

The group on the Alice, estimated to number about 700 when white settlement began, was reduced to 136 by the time Barcaldine was established. They were said to be a superior people, some over six feet tall and with a life span of 90 years. Their customs were similar to those of other inland tribes – they scarred back and shoulders, were polygamous and had no marriage ceremonies. Unlike many tribes, they did not practice circumcision as a maturity rite. Dead males were buried for a time, then disinterred and the bones carried in a bark coffin for several months before reburial. [v] Although nomadic, they built, as Mitchell saw, quite substantial semi-permanent shelters.

White Settlement

A Queensland Land Act of 1860 allowed settlers to take up runs of 50 to 10 square miles with no limit to the number that could be acquired by one owner. Fourteen year leases were granted if settlers stocked to within one quarter of carrying capacity within one year. The law was a formality, impossible to enforce in the early days. The Mitchell district was a frontier. Holders of leases did not necessarily live on their land and some runs were never formally leased. Clashes with the natives were not documented but the natives and their culture were soon destroyed.

Reports to parliament by the Commissioner of Police show that a police station opened at Aramac in 1872. The following year it was stressed that native troopers should be brought from the south for a time and then returned because it was

‘vital to keep this branch of the force thoroughly efficient . . . for checking the Aborigines in their outrages’.[vi]

In 1873 there were nine native troopers at a camp on the Barcoo River but by 1875 letters in the press began calling attention to atrocities committed against Aborigines and the public furore that followed led to phasing out of native police. In 1879 the camp at Blackall was broken up, although use of black trackers was retained for many years.

Natives who survived this pioneer warfare were adopted by various stations and became a means of cheap labour, men for stock work and wood cutting, women for laundry and house cleaning. A few remained in the bush.

The first settlers in the area of whom records exist were J. T. Allen of Enniskillen to the south and John Rule and Dyson Lacy of Aramac Station to the north.

In 1863, Donald Cameron, his son John, and James and William Crombie overlanded sheep from the New England district of New South Wales and pastured them along a forty mile frontage to the Alice River. They called their homestead block Barcaldine after a family property in Scotland and named others Glen Patrick and Cedar Creek.

Leases were granted to them in 1865. By then the group had built a home of split slabs on Hazelwood Creek with strong bolted shutters and loop-holed walls for protection against Aboriginal attack. Donald Cameron brought his family to live there in 1866 and in time his eldest daughters married the Crombie brothers.[vii] At first Springsure, more than 200 miles away, was the nearest town and their neighbours were at Alice Downs and Coreena but within a few years all available land in the area was taken up and townships began to develop at Tambo, Blackall and Aramac.

Teamsters, drovers and itinerant workers blazed tracks linking these centres, wandering from one water hole to another until defined roads led from Tambo and Blackall past Home Creek, Lagoon Creel and Saltern Creek to Aramac. At suitable camping places grog shanties and wayside pubs appeared and a fairly substantial inn on the south bank of the Alice became an important stopping place for many years.

By 1869 drought forced the Camerons and Crombies into serious debt and T. S. Mort, to whom they owed money, involved them in a partnership with J. T. Allen and Herbert Garnett. The company, known as J. T. Allen and Partners owned Enniskillen, Birkhead, Vergemont, Home Creek and Barcaldine Downs. Camerons and Crombies became unpaid managers for Mort and answerable to Allen, known as Black Allen, whom they intensely disliked. Donald Camerson moved to Home Creek with his family, leaving the Crombie brothers at Barcaldine Downs. Broken in health and spirit, exiled from the block he had pioneered, Cameron died at Home Creek in 1872 and was buried there.[viii]

The next decade brought prosperity for the others and in 1877 they were able to break free of the partnership by selling Barcaldine Downs and Home Creek to George Fairbairn and buying land in other parts of Queensland. Ten years later Mrs Cameron retired to a grand residence in Toowoomba which she called ‘Fairholme’ and which ultimately became a Presbyterian Girls’ College. Descendants of Cameron and Crombie families still lived in western Queensland in 1985.[ix]

Land and Power

Land registrations of the Barcaldine district in the 1870s were:[x]

- Barcaldine Downs and Home Creek: J. T. Allen and Partners (from 1969). George Fairbairn (1877).

- Coreena: John Rule and Dyson Lacy (from 1863). Oscar de Satge and Hamilton Milson (1874).

- Avington: Charles Lumley Hill, John McLean, William Beit (1874).

- Delta: William Scafe (1876).

- Evora: Thomas Henry (1874).

- Saltern Creek: Edward Weinholt (1874).

In some cases there were renewals of earlier registrations.

The government passed a new land act in 1884, under which all blocks were to be properly surveyed and leases consolidated into registered holdings on which payment of rent could be enforced. Under its provisions each large property lost a portion, resumed for closer settlement.

The work took time and in the Barcaldine area, consolidation coincided with the birth of the town – 1886.

Three previous years had been harshly dry causing indebtedness to banks and finance companies as the new registrations show. These were:[xi]

- Barcaldine Downs (179 sq. miles resumed, 321 sq. miles of lease) – Union Mortgage Co.

- Home Creek (335½ sq. miles resumes, 360 sq. miles lease) – George Fairbairn.

- Coreena (400½ sq. miles resumed, 753 lease) – Australian and New Zealand Mortgage Co.

- Avington (221 resumed, 272 lease) – William Oliver and Robert Smith.

- Delta (124 resumed, 395 lease) – Robert Smith.

- Evora (134¼ resumed, 264 lease) – R. Goldsborough and Co. (later Goldsborough Mort).

- Saltern Creek (149 resumed, 313 lease) – Henry Edward Hill.

After consolidation Barcaldine Downs and Home Creek were run as one property and all stations retained use of their resumed portions for some time. Most of the new blocks were thrown open in 1890 but that year was so wet little progress could be made in resettlement.

Station Life

At that time the big stations were like small townships, each with its own store, blacksmith, and butcher shop. Managers and owners had absolute power. Workers were obliged to buy rations from the station store and shearers were paid only for sheep shorn to the owner’s satisfaction, shearers and shed hands lived in tents or primitive huts with dirt floors.

An account of shearing at Barcaldine Downs in the Brisbane Courier, April 4, 1888 gives a picture of typical station life.

The main homestead was lined with varnished cypress and had a double roof which made it cool. Outbuildings included a large store managed by R. Wilson and a butcher shop where a bullock and several sheep were killed each day at shearing time to supply about 150 men. A.J. Rodgers was manager in 1888. His predecessor, George Johnston, had established a fine garden although drought and white ants had ravaged it. The country had little natural water but a great deal of money had been spent on dams and wire fencing, with water from the homestead drawn from Hazelwood Creek. Near the shearing shed about three-quarters of a mile away tents were scattered over a wide area and three hawkers plied a trade with wives of shearers. A large bough shed about 100 yards from the shearing shed made a place for meals. The property ran about 220,000 sheep in 1888 and had space for 80 blade shearers, who averaged about 100 sheep a day. Jackie Howe may have been in a team. Howe shore 321 sheep in one day with blade shears at Alice Downs in 1892 to create a world record. In the same year, he shore 276 sheep at Barcaldine Downs with machine shears, installed there in 1890. In 1888, much of the wool from Barcaldine Downs clip was hand washed near a dam on Andrew’s Creek by a contractor named McKewen. The arduous task of hand washing gave way to mechanical scouring after a plant opened in Barcaldine in 1893. Although machine shears were installed at some sheds prior to 1891, their use does not seem to have been a matter for contention.

Working conditions, rates of pay, and use of coloured labour were issues that led to the shearers’ strike.

Endnotes

[i] T. L. Mitchell. (1848). Journal of an Expedition into the Interior of Tropical Australia. Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans: London.

[ii] W. H. Trail. (1886). Historical Sketch of Queensland. Sydney.

[iii] J. T. S. Bird. (1904). Early History of Rockhampton. The Morning Bulletin: Rockhampton.

[iv] N. B. Tyndale. (1974). Aboriginal Tribes of Australia. Australian National University Press: Canberra.

[v] E. M. Curr. (1886-7). The Australian Race Vol III. Melbourne Government Printer: Melbourne.

[vi] Queensland Parliamentary Votes and Proceedings. 1872-79.

[vii] M. Reeves. (1985). A Strange Bird on the Lagoon. Boolarong: Brisbane.

[viii] Records of Lands Department. Mitchell District. For 1870s – LAN/N2A and LAN/N2B. For 1886 – Barcaldine Downs LAN/AF 696, Home Creek LAN/AF 726, Coreena LAN/AF 711, Avington LAN/AF 695, Delta LAN/AF 695, Delta LAN/AF 714, Saltern Creek LAN/AF 761. Queensland State Archives: Brisbane.

[ix] The Capricornian: Rockhampton. 1886-1891. See dates in text.

[x] The Diamond Jubilee of the Worker. (1950). Souvenir Number. Worker Newspaper Pty Ltd: Brisbane.

[xi] W. Ross Johnston. (1982). The Call of the Land. Jacaranda: Brisbane.

Text sources include: Hoch, Isabel. (2008, 3rd edn). The Barcaldine Story 1846-2008. Barcaldine Shire Council, Barcaldine.