For more than one reason, Barcaldine was destined to become an important town. If the shearers’ strike had not occurred, it would still have had a lasting place in its country’s history and for a happier matter – the discovery of artesian water. The first freely flowing deep artesian bore of Queensland was sunk a few hundred yards from the railway station within one year of the town’s establishment. It was hailed throughout the country with joy as being a discovery more important than gold, for artesian water was the liquid gold of the outback without which no development could take place.

From 1883 when the railway was first pushed across the Drummond Range, life along its course was made miserable by lack of water. Three years of drought turned the land to dust and desolation, brought chronic ill-health and slowed progress of the line. After contractors, O’Rourke and Aherne reached Alice in December 1885, drought and shortage of rails brought work to a standstill for months. During that time, there were about 300 residents at Alice, served by five licenced hotels, various stores and a post and telegraph office. Poverty and idleness allowed social problems to develop. The problems intensified at Richmond, a canvas town about five miles west which supplied ballast. It became a breeding ground for petty crime and sale of sly grog and Richmond residents kept the courts busy until the settlement was disbanded in July 1887.

A buyer at each of the sales, A.J.A. Moody, manager of the Queensland National Bank, travelled by buggy from Alice in May 1886 to inspect progress along the line. He reported to the General Manager in Brisbane that a bore had been sunk by the government at Back Creek, using a diamond drill and that the flow of 50,000 gallons a day had been struck. Though little reported at the time, the discovery was an exciting portent. Back Creek bore was only 180 ft. deep and the overflow was slight but the government was encouraged to continue the search for underground water.

In September 1886, the Government Hydraulic Engineer, J. B. Henderson, visited the fledgling township of Barcaldine and reported to parliament that many buildings were in course of erection. He suggested several possible schemes for water supply and recommended Alice River as the best, stressing a need to proclaim a reserve there to protect the hole from pollution. A Chinese garden, a saw mill and a dairy were already using it.

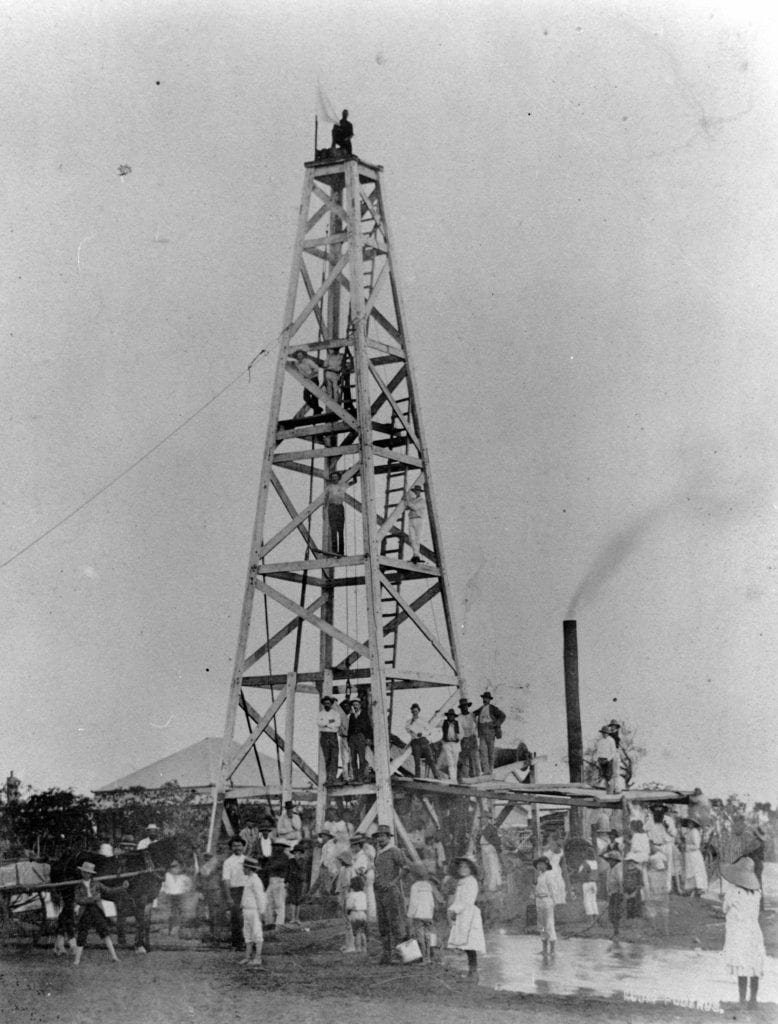

In 1887, the government engaged a Canadian, J.S. Loughead, to probe to 2,000 ft. if necessary, at Barcaldine and at places 20 miles and 40 miles further west along the proposed railway, in a determined search for artesian water. Work began near the goods shed on November 18, 1887 and in the third week of December reached triumphant success. A correspondent to The Capricornian reported

The drill of Mr. Loughead’s plant suddenly went down and with a spurt, water overflowed the top of the casing and commenced running all over the float. Particles of rock and shale came to the surface and from dirty brown the water changed to crystal-like hue.

Within a few days the tidings had spread throughout the district and people were coming in from all directions to see the miracle of flowing water which had cut a channel for itself into Lagoon Creek, filling all the holes as it went. The triumph was made sweeter by the fact that Barcaldine had beaten Blackall to the great discovery. A deep bore at Thurulgoona near Cunnamulla struck water before Barcaldine but it had barely overflowed and had to be pumped. In December 1887 Barcaldine had the first free flowing, fully successful, deep bore in Queensland.

In January 1888 connecting parts for the bore were assembled, watched by graziers Fairbairn from Barcaldine Downs and Hopkins from Wellshot. It was not long before these men put down bores on their properties and with a few years there were hundreds of flowing bores in Western Queensland.

In March 1888, the Premier, Sir Samuel Griffith, came to see the first bore sunk in Barcaldine.

Artesian Bores

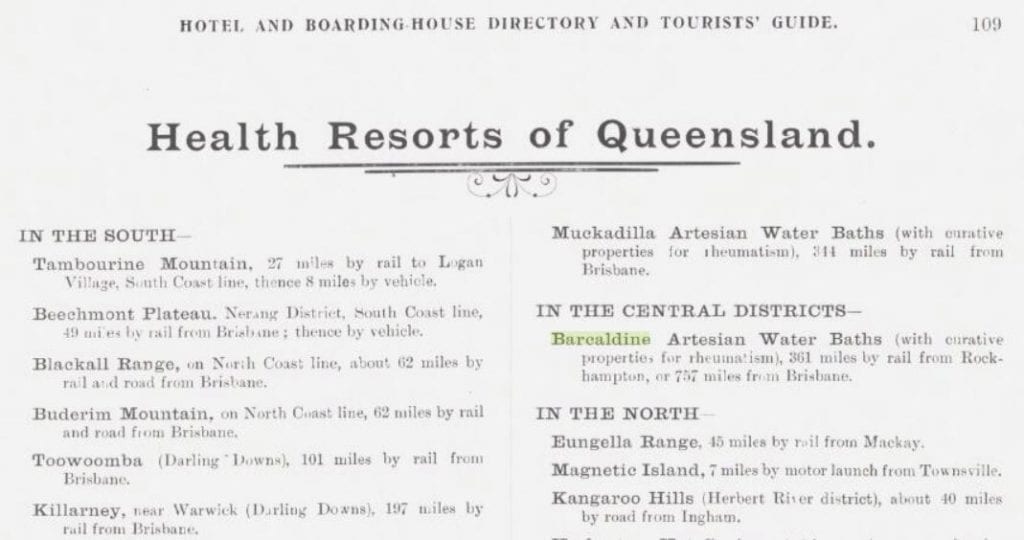

Of our institutions the first is, of course, the bore. Although cast in the shade somewhat by the subsequent discovery at Blackall, still we may speak of our bore with a great deal of pride, for was not the first artesian water ever struck on the Barcoo found at Barcaldine? Through the energy shown by the Member for the Barcoo, Mr. F. R. Murphy, the Government decided upon putting down a bore at Barcaldine by means of the pole system introduced by Mr. J. S, Loughead, and the railway reserve, between the triangles, was chosen as a suitable site. After about three weeks’ actual work, water was struck at 645 ft. on the evening of Friday, the 16th of December, 1887, and boring was continued until 690 ft. was reached when operations ceased, the water flowing over the surface of the 12 in. diameter pipe. The water is 101° Fahr., is perfectly clear and soft, and very slightly mineralised with sulphur and magnesia. Upon tests being made the outflow was found to equal 175,000½ gals. per day ; the water was compressed into a four-inch pipe, and runs away by means of a goose-neck. The bore is surrounded by a canvas screen, and the inhabitants and visitors bathe without let or hindrance. The water is used by house holders for all purposes, and the overflow runs down Lagoon Creek, and has reached the Alice River, four miles away, where it runs a perennial stream. Mr. Longhead believes he has struck a basin of moving water, (the smooth pebbles brought up by the first flow of water point to running water), that pillars of rock hold up the cap rock, making the cap rock a series of arches as it were, and that probably this basin or running lake extends for many miles.

Western Champion 3 September 1888

The first Barcaldine bore cost £1219.13.3, was 691 ft. deep and tested at 175,416 gallons a day.

Its fame spread quickly and people allowed to bathe in the pool which formed around the derrick claimed wonderful properties for the mineral charged water. Sore eyes, fevers and even paralysis (in the case of Mr. Lilyman from Jericho) were said to disappear. The water was tested and its quality proved suitable for a brewery and there was talk of establishing a wool scour or a meat chilling plant. Ironically, though, the water was never really suitable for use in the steam engines for which the bore was originally sunk.

Afterwards a fence was erected around it and a caretaker put in charge, but he was not highly regarded. The newspaper reported that he drew a good salary for doing ‘nothing more than roam the streets with his hands in his pockets’ and it was not long before the surrounds of the bore were no longer fit for ladies’ bathing.

It seemed that the people of the railway, so long deprived of water, hardly knew how to use the abundance they had suddenly acquired.

Cleanliness, as it is understood now, was non-existent. Hotels did not have bathrooms and in their own homes Barcaldine residents only washed themselves about once a week. It is not surprising that illness was prevalent.

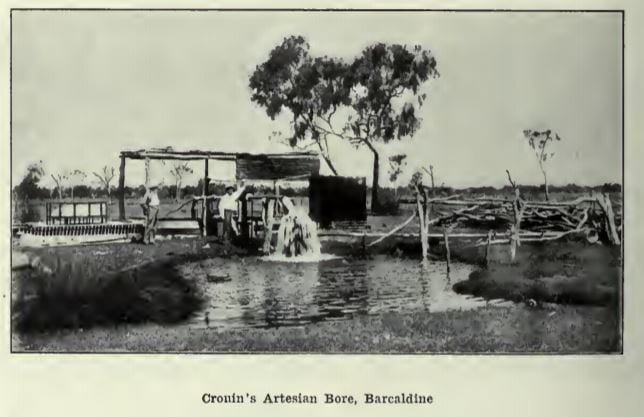

The summer of 1892-3 was dry and the railway department guarded in supply of water from the government bore. Contractors, Brown and Mackenzie were engaged by the new Divisional Board to sink a bore in Ash Street and by April 1893 a ‘pure and abundant’ flow of 528,000 gallons per day had been obtained at 1,300 ft. Unfortunately the colony was thrown into debt that year by overborrowing from English banks in the previous decade. There were ‘dishonoured cheques everywhere’ and banks closed to trading from May to about August. The planned development of water reticulation in Barcaldine had to wait until 1895 before money became available.

Pipes were laid up Oak and Ash Streets that year and in August a poll of ratepayers approved a loan of £500 to extend the scheme. Barcaldine became the first town of western Queensland to have reticulated water but pressure from the bore could not keep up with the demand. When summer came the mains had to be turned off at night to allow a flow into Lagoon Creek for stock and by 1898 such a crisis had arisen that a public meeting was called. Democratically, the Board members explained to ratepayers that water was leaking outside the bore casing and a new liner had not cured the problem. Calling it ‘the most serious matter ever put before ratepayers’ they announced a poll to decide if £1,000 should be borrowed for a new bore. The result was two to one in favour.

In May 1899 a flow of 500,000 gallons a day was struck at the corner of Yew and Pine Streets on the Queen’s birthday holiday at a depth of 1,422 ft. A first supply of poorer quality water was shut off at 660 ft. The Yew Street bore was still in use 87 years later.

From the time the Yew Street bore was struck in 1899, the Divisional Board intended to clear obstruction from the one in Ash Street but drought and lack of funds made the attempt impossible until 1904. The result then was only fair – a flow increased by about one fifth of the original amount although it was deepened to 2,681 ft.

Need for water storage

Pulling down of buildings was the only way to stop a fire in the early years because increased demand allowed water pressure to fall away in household mains. Little more than a trickle came from taps much of the time. No showerbaths could be taken and at night the flow was sometimes turned off altogether. Water never reached the top storey of hotels, to which all water for washing had to be carried upstairs. Afterwards it was tossed over balconies into the open sewer.

After the 1896 Oak Street fire, the urgent need of water for fire fighting purposes was recognised.

In May 1913, the tender of Barbat and Sons, Ipswich was accepted for the construction and erection of a solid steel tower and tank as part of the Barcaldine water supply system. The tender for the Barcaldine water tower and tank was for £3,495 5s 4d. The tank was decorated in a chequerboard pattern.

The township depended on prosperity of the pastoral industry and felt dire effects in its business houses in the drought that brought hard times after 1925. By August 1926 the town had registered only 5.62 inches in the previous 11 months and even trains had difficulty in getting through – water for the steam engines was unavailable at Jericho and the Barcaldine bore water was not suitable. Relief came to some districts in October but the wet season failed again in the central west and by May 1927 the country from Longreach to Barcaldine was described as utterly bare:

‘Not enough feed for a grasshopper’ the newspaper stated. ‘No birds. No kangaroos’.

Graziers purchased motor trucks to deliver hay, maize, salt and new processed ‘licks’ to their dying stock but the drought went on too long and many found themselves reduced to unpaid managers for financial institutions.

Commitments made before the drought brought many urgent problems to the council. A large loan had been negotiated with the Treasury for a power and water scheme. Water flow from the Yew Street bore was down to 70,000 gallons a day when work began, but by May 1927 the bore was cleaned out and the flow almost doubled. New concrete mains and a new pump were installed and a deep well sunk for storage. Unfortunately, cracks around the well allowed water to seep away faster than it could be pumped in. The situation reached crisis in mid-1927 when funds were exhausted. The Council refused further responsibility and the Irrigation Department took over repair of the well.

In 1936, the water mains were renewed. They were supplied by Hume Pipe Co. and cost about 9,000. Minor contracts were let to J. A. Whitfield.

Work on the water scheme was hindered by heavy wet seasons.

Plan for weir

In an effort to assist the citrus and grape growing industry, the Shire Chairman, C. Lloyd-Jones, advocated for a state financed weir on the Alice River. In November 1952 work began on a Department of Irrigation and Water Supply project believed to cost approximately £50,000. About 33 men were employed, many of them New Australians (as migrants were then called). Some had wives and families and all lived in pre-fabricated buildings at the site. The weir was complete by October 1953 and handed over to the Barcaldine Shire Council for maintenance.

It overflowed for the first time in January 1954 but Lloyd-Jones, for whom it was named, did not live to see the fulfilment of his 15 year old dream. He died on 19 December 1953, having been chairman for 23 years.

The rain soaked fifties were a severe test for the weir and major repairs were required after its first filling, in March 1955, and again in January 1956. The work was carried out for the Department of Irrigation and Water Supply under the supervision of council engineer, C. H. Wilson. The Lloyd-Jones Weir became a popular place for fishing and picnics and provided some irrigation for farms and orchards but has not become the centre of development that was ambitiously predicted in its early years.

Need for better water supply in town

By 1956, the council was faced with a need to provide better water supply in the town as flow from the original Ash Street bore dropped back. It had never been cased below 1,672 ft., the water was of high temperature – 180 degrees F and after 1953, it was not used. The old bore at McLaughlin’s wool scour was also shut off about 1953. Council accepted a tender from Godfrey Bros. of Blackall for a bore at the new power house and flow was struck at 1,201 ft. In 1957 it was measured at 20,800 gallons per day and it still flowed when the pump was withdrawn for testing in 1965. The tests were made to examine the pump because the shaft of the bore was not straight, having a bend at the 40 ft. level apparently caused by cross-threading of the casing. Although this bend caused stress on the pump drive shaft, it was not a major problem. In 1985 water for Barcaldine town supply came entirely from the two bores put down in 1899 and 1956.

Tree planting was always important to Barcaldine, limited only by availability of water. Through the dry years of the late sixties the 1956 bore near the power house had to be pumped constantly. High operating costs and fear of pump failure led the council to request the department of Local Government for a survey into all aspects of its water supply. The investigation was undertaken in 1968 and a comprehensive report submitted to council. It provided a valuable history of artesian operations in Barcaldine to that date. Findings of the survey included the optimum fluoride content of the Yew Street bore (further proved by the healthy teeth of permanent residents), the wastage from leaking mains that is not always apparent in the sandy conditions, and a local practice of running taps overnight in winter to maintain hot water.

Unmetered supply made this a cheap alternative to hot water systems. It is not surprising that Barcaldine proved to have the highest per capita water consumption of the state. Meters were recommended but were introduced only gradually. By 1985 all public buildings and recently constructed homes were metered. Water for the town came directly from the bores with the elevated tank used only as a balance tank to save mains from pressure damage. Barcaldine water was non-corrosive and always pure, with no storage area where pollution could occur.

In 1991 a Bore Replacement fund was created but it was not until 1996 that a new supply became a reality in Acacia Street, sunk to a depth of 464.45 metres. It was connected to the main water supply and pumped at the same rate as the old Pomona bore to minimise interference of flow between the two.

In 1993, when work began on Stage 2 of the Australian Workers’ Heritage Centre, the expansion included a billabong. The landscaped billabong was made possible upgrading the old Ash Street bore to supply most of the Centre’s water, so as not to draw heavily on the town’s supply and Water meters were installed in Barcaldine and gradually in other towns in the region. Both bores were equipped with electric pumps and the iconic water tower, although no longer filled with water was maintained in good condition to serve as a communication tower.

The dry years and leakage of the Pomona bore eventually forced water restrictions. A new bore was an urgent need and council succeeded in receiving $1.7 million from the government through a Smaller Communities Assistance Program to allow its construction in 2002. The bore was put down near the old Pomona site by AFRAC Drilling to a depth of 459.8 metres allowing a flow of 37 litres per second.

In accepting the grant for a new bore Barcaldine Council was obliged to borrow for other infrastructure. $1.3 million was spent to upgrade the majority of water mains, construct a reservoir at the Acacia Street bore site and acquire variable speed pumps to improve water pressure.

Text sources include: Hoch, Isabel. 2008. Pages 135, 139, 141, 157, 159