What triggered the 1956 Strike?

‘In early 1956, the Federal Industrial Court and the state Queensland Industrial Court agreed to a demand by the pastoralist industry to reduce the rates of pay for shearers around the country. After a rise in wool prices due to the Korean War, prices had again started to slide and the graziers argued they could no longer afford to pay a prosperity loading to shearers.

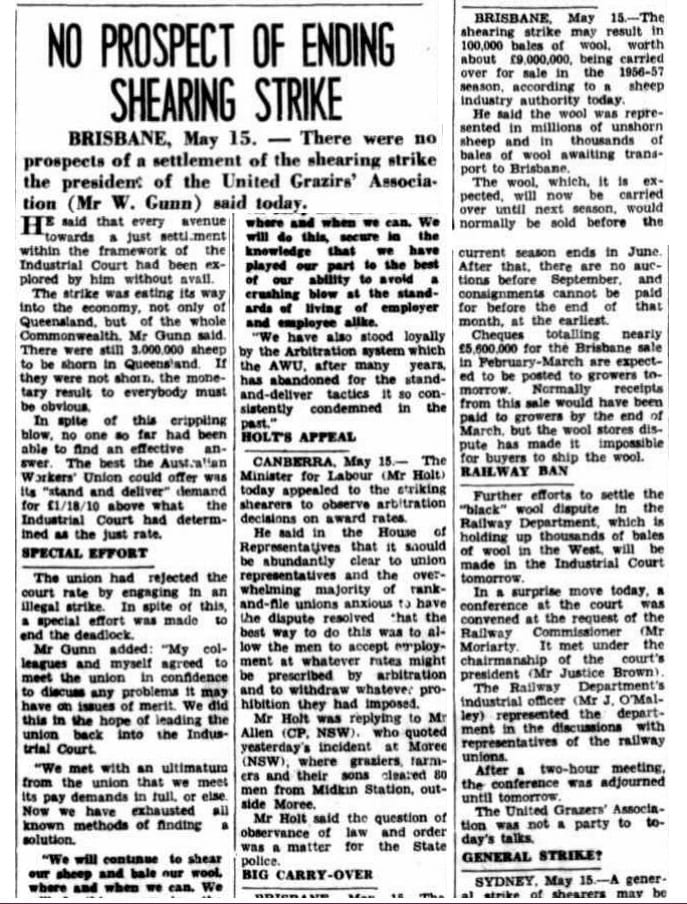

What occurred next was one of the most protracted disputes in the industry’s history with the Australian Workers Union calling on all shearers to refuse to work for anything other than the old rates of pay. Joe Bukowski, then the secretary of the AWU in Queensland issued a statement saying, “if I were a shearer I would not shear at the new rates,” while Bill Gunn, president of the United Graziers Association, issued a call to the graziers- “you are in for the fight of your lives”.

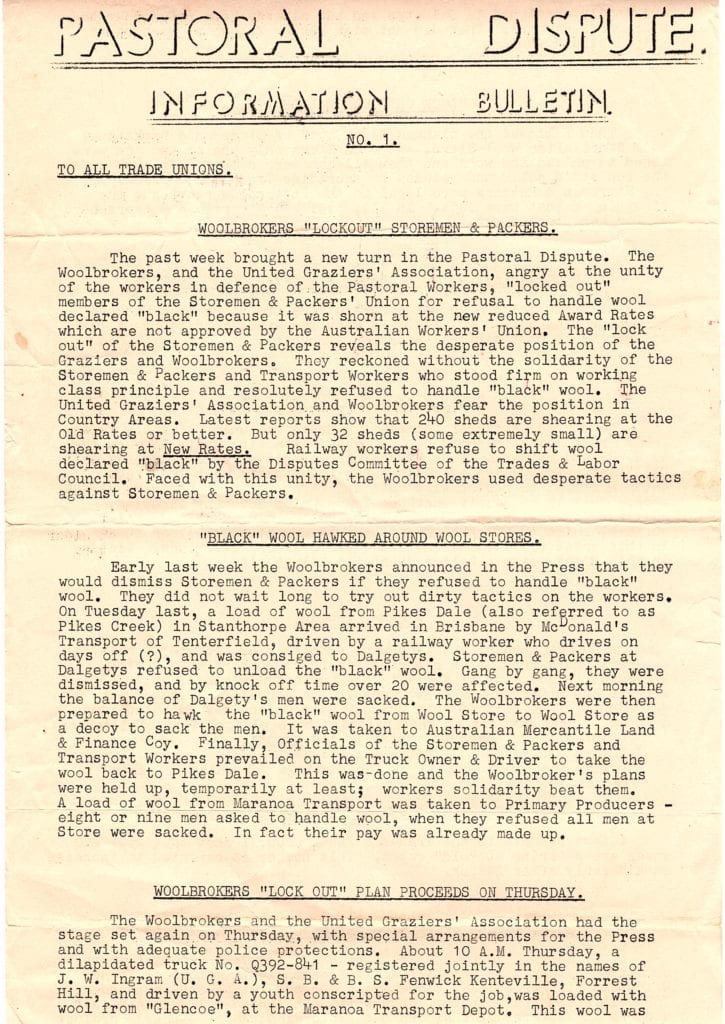

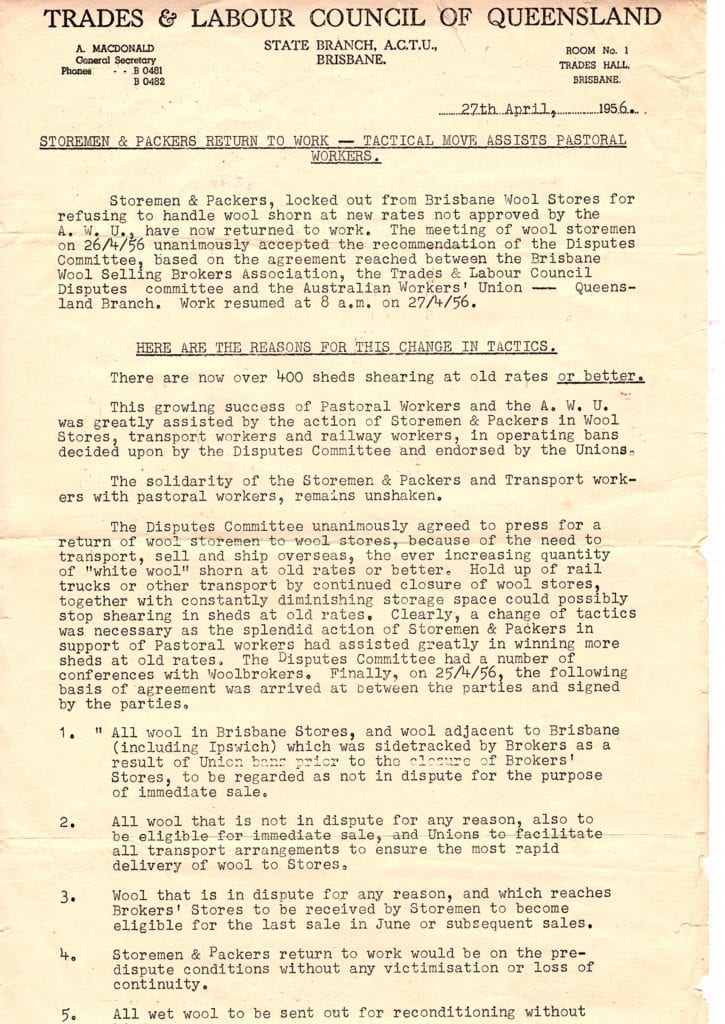

The dispute pitted “old raters” against the scab labour of “new raters” and was marked by violence in many shearing towns throughout the country. The railway and maritime unions went out in sympathy and refused to transport “black” wool that had been shorn on the new rates’.

The fifties were such wet years that sheep men had to battle to save their stock from fly strike, worms, lice, water logged feet and burr infested wool.

In March 1950, The Longreach Leader reported 40,000 sheep lost from fly strike in the Aramac district alone.

By 1954 nine properties on the east of the shire were reported to be stocked with cattle.

But wool was so valuable at that time that graziers attempted to retrieve the fleeces from dead animals and pack them for sale.

As nations built up stockpiles of wool, prices began a downward slide. In response to a request from the United Graziers’ Association, a 10% reduction in the shearing rate was ordered by the Arbitration Court to take effect from January 1956.

The shearers resisted, and the industry plunged once more into a strike. This time it dragged on for ten months through one of the wettest years the country had seen. It was a sophisticated struggle without the dramatic confrontation of 1891 or the deep bitterness of 1931.

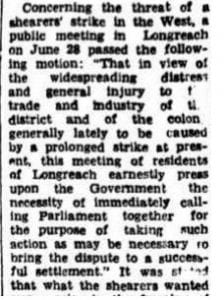

Letters to the press argued that the strike was against the principle of arbitration and that the premier, Vince Gair, was weak for his non-intervention. E. T. Towner, VC winner from the 1914-18 war, wrote that shearers had reached the antithesis of the code they fought for in 1891, for they now wanted freedom of contract – freedom to set down their own rate of pay instead of that laid down by the Arbitration Court.

For the pastoralists however, it was a different story, a time of great uncertainty. It held up the shearing for months on end.

Seeking to circumvent the stike action, the graziers formed their own shearing gangs to get the work done. That meant learning new skills such as shearing and wool classing.

Led by UGA leader, William Gunn (later Sir William) graziers, managers, overseers and their sons formed voluntary teams to shear their own sheep and those of their neighbours. When railway workers refused to handle wool, it was transported by other volunteers and in some places stored under armed guard.

The graziers were helped by scientific refinement of DDT based preparations which made it possible to protect wool from fly strike.

The graziers held out and by the time winter was over almost 80% of the shearing had been done by volunteer teams.

When wharf labourers struck, more volunteers were organised to load the ships.

The strike lasted from January 1956 until October in Queensland – NSW and Victoria had finished earlier in the year.

The shearers and the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) managed to get the old rates reinstated, so it was seen as a major victory for the shearers and their union.

The Barcaldine Story - 1956 Shearers Strike

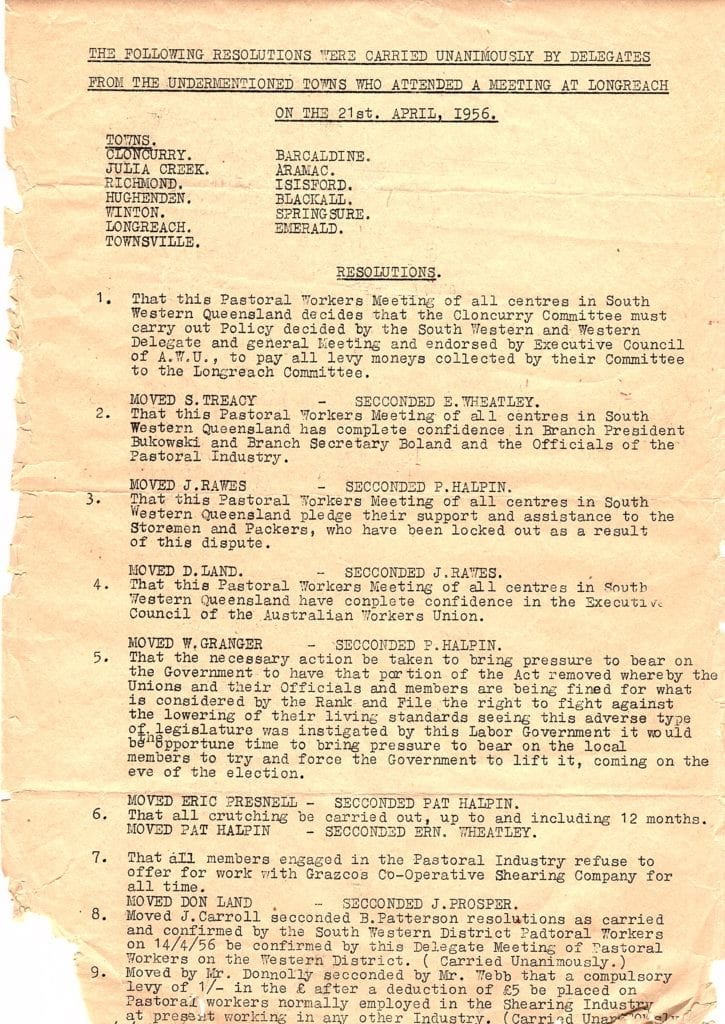

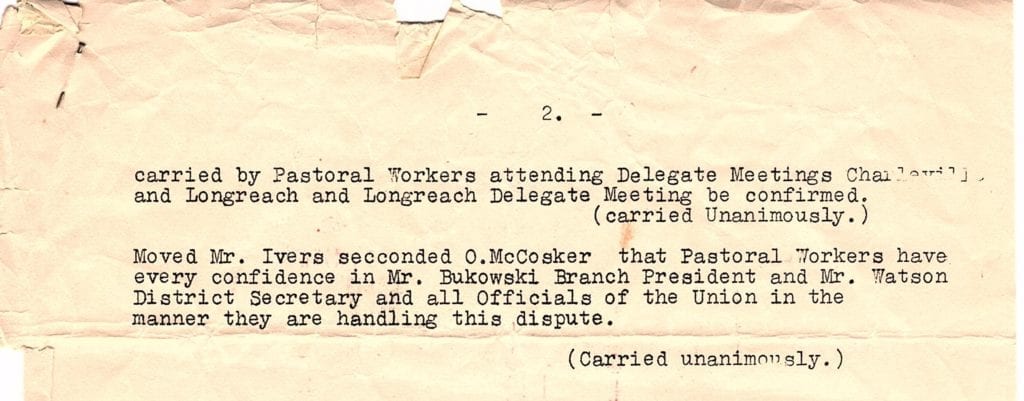

The work of the Strike Committee

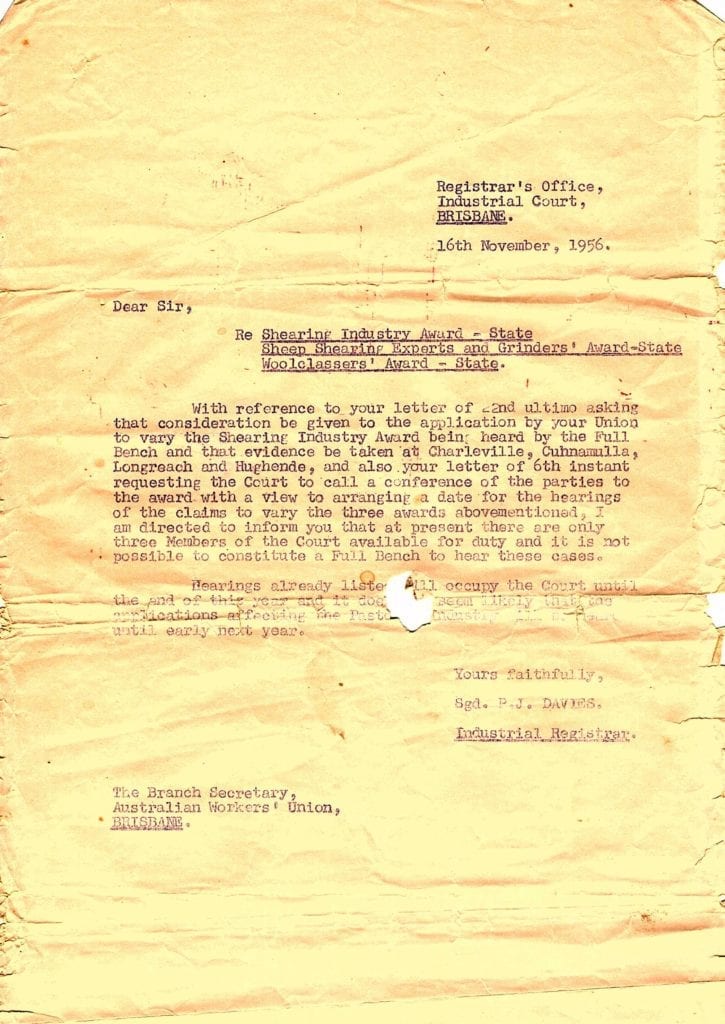

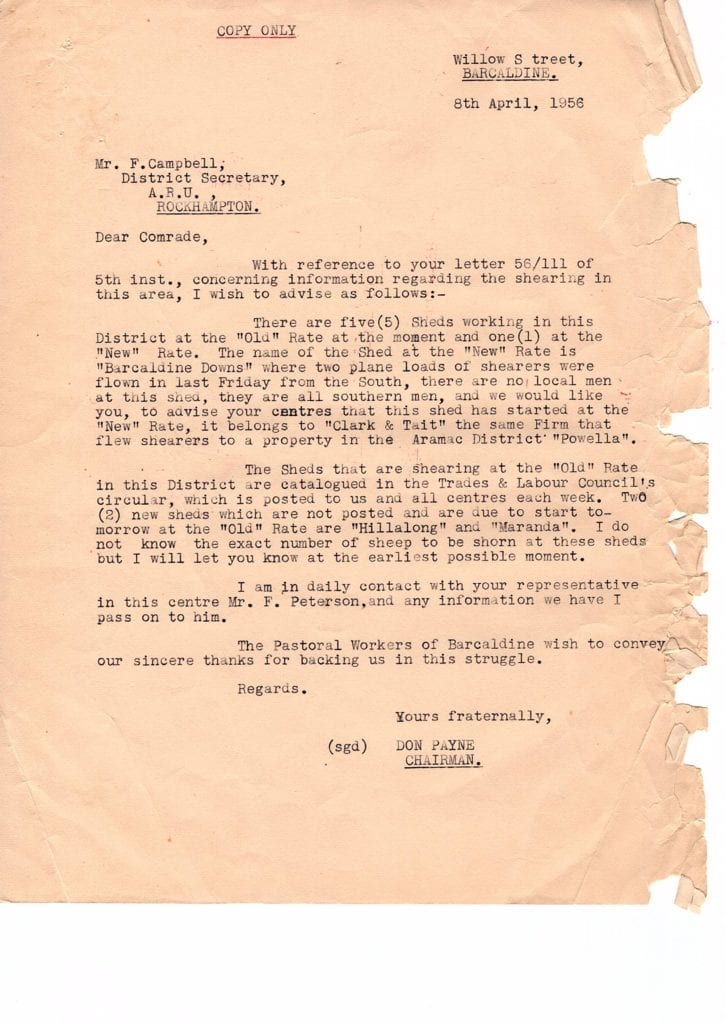

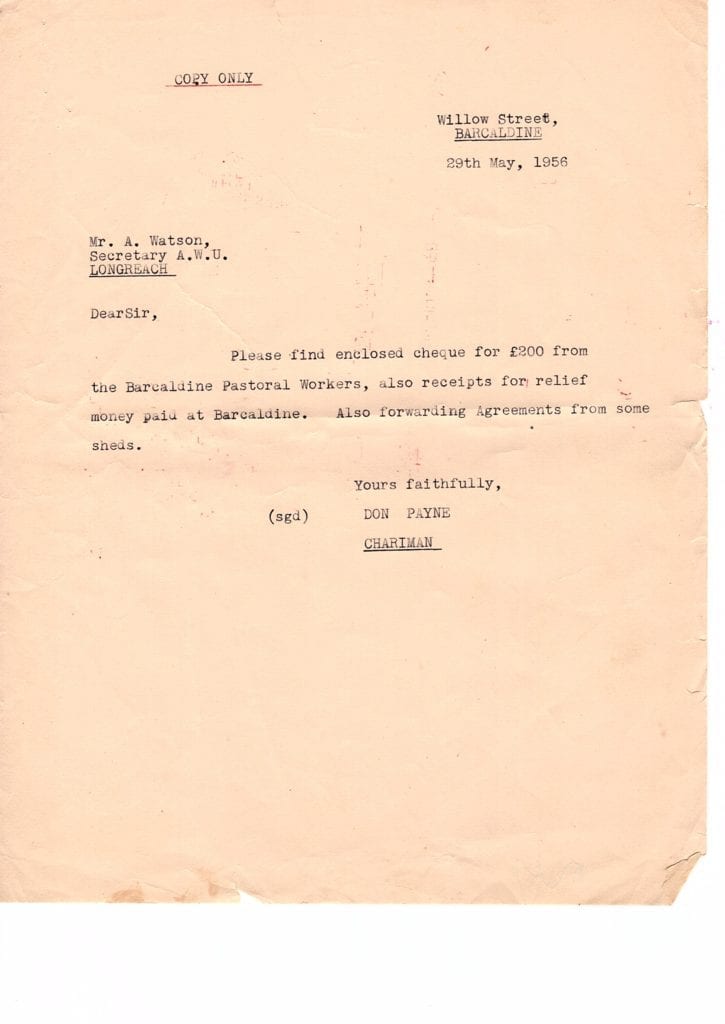

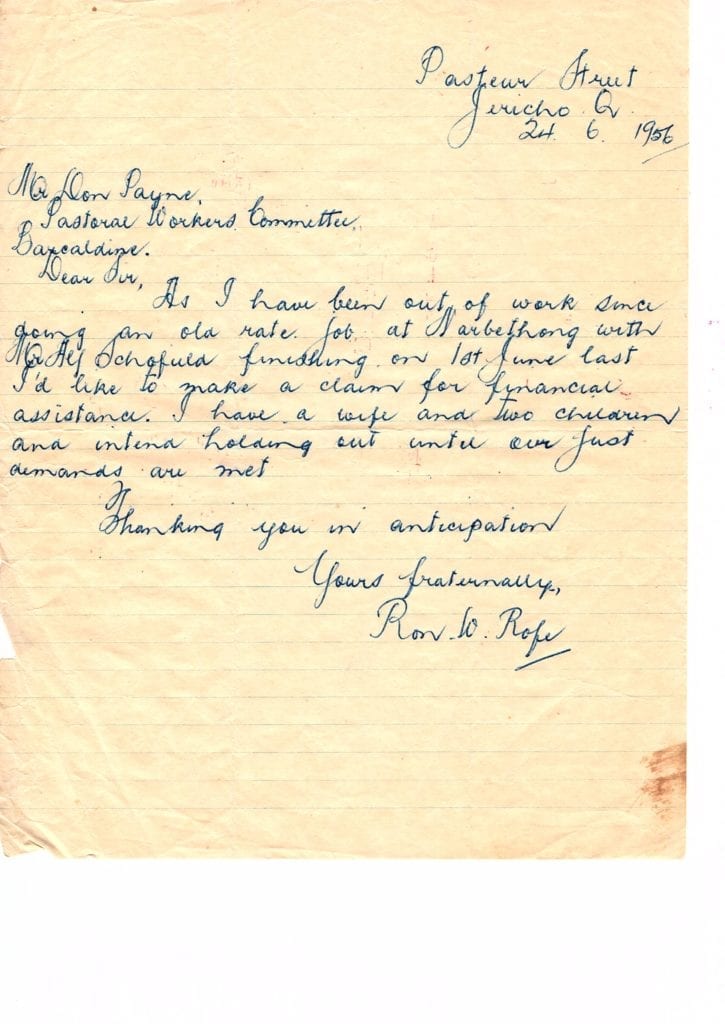

The following account of the 1956 shearers’ strike is drawn from original documents donated to the Barcaldine and District Historical Museum by Fay Payne.

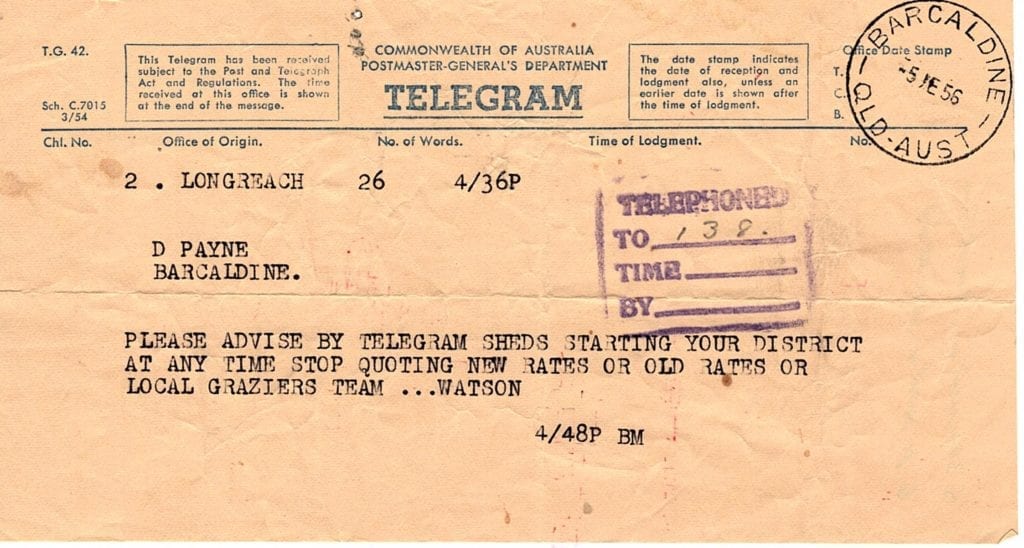

Fay and her husband, Don Payne (a shearer), were involved in the wider dispute at the local level in Western Queensland.

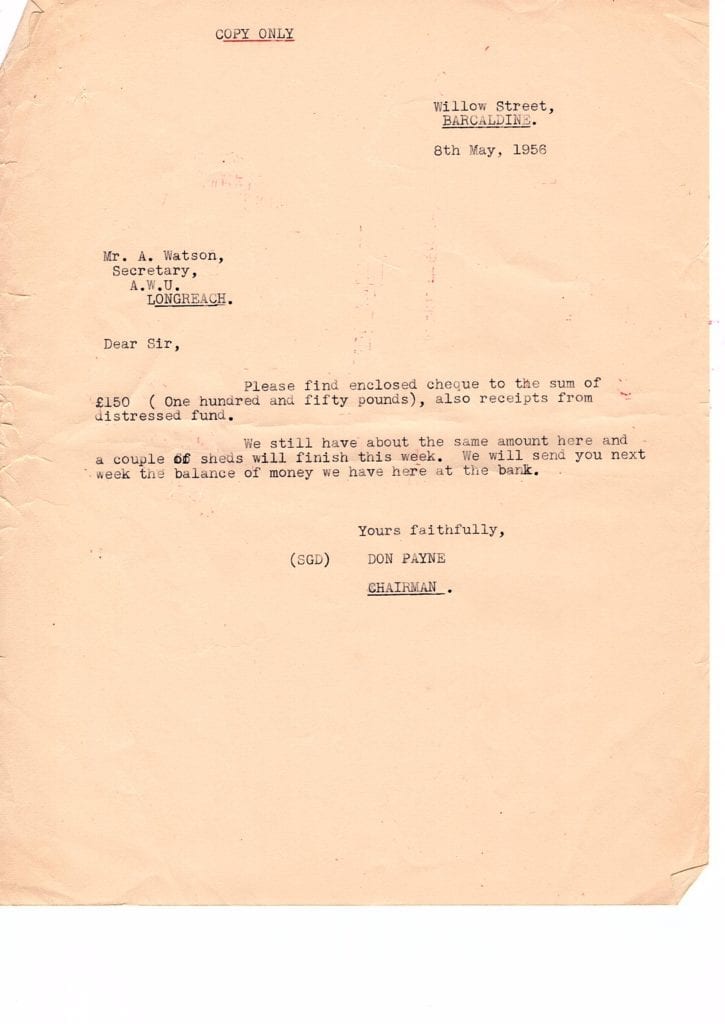

Don was the Chairman of the local strike committee, and Fay was his assistant typing up correspondence and notices pertaining to the strike activities. They lived in Barcaldine, the scene of the 1891 Great Shearers’ Strike.

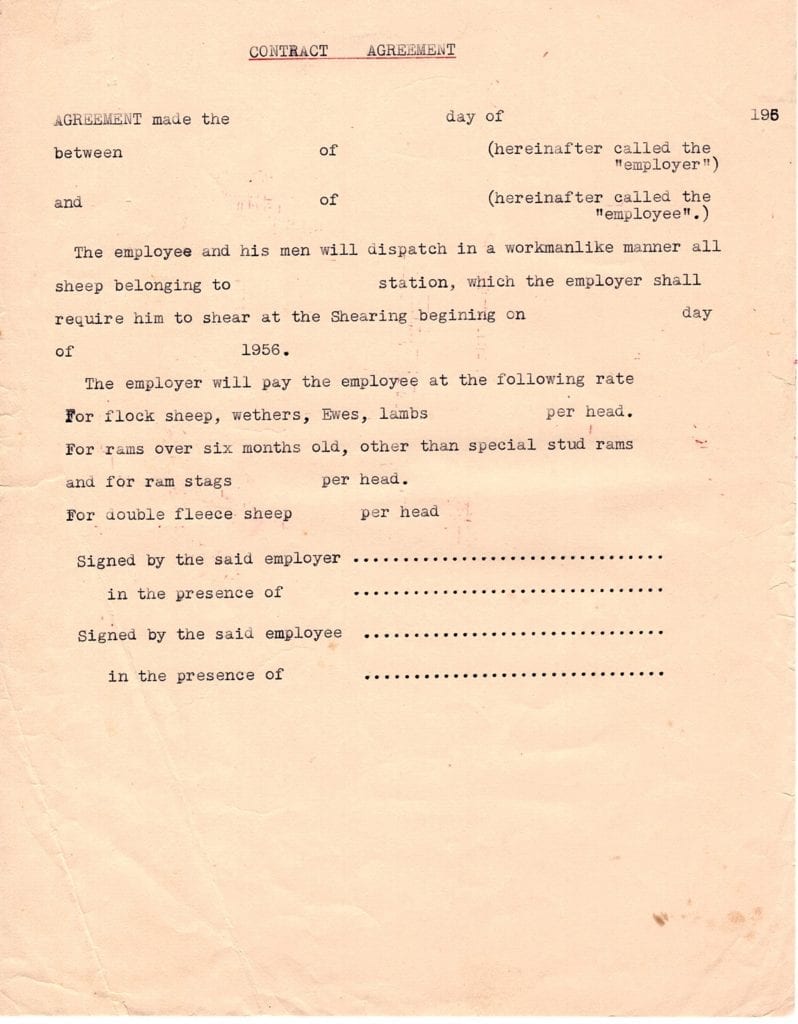

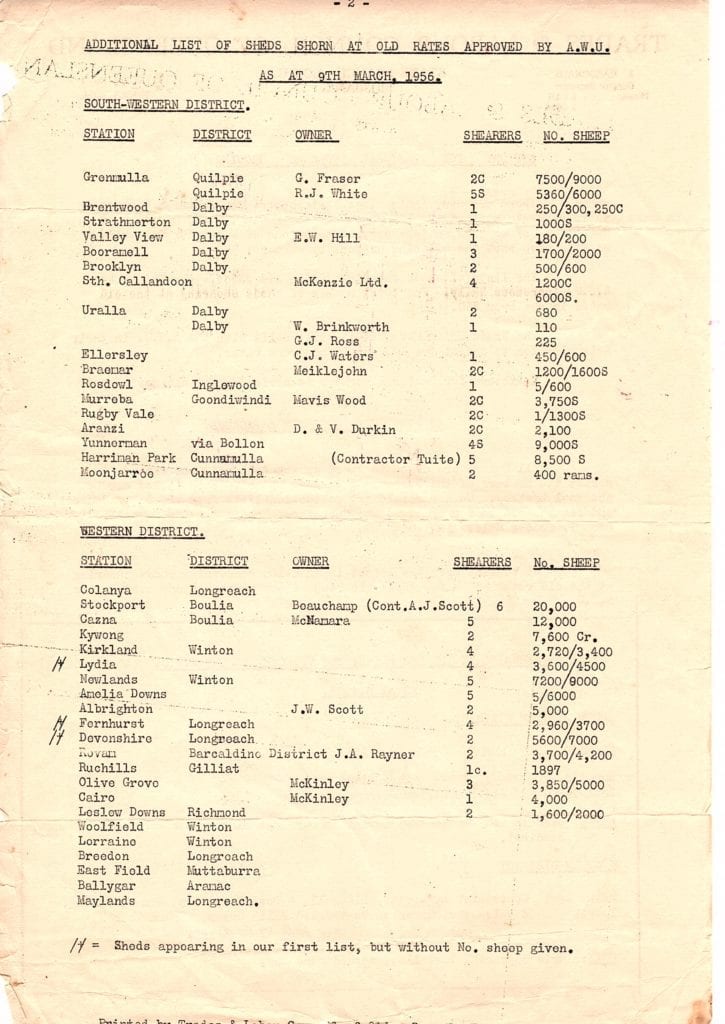

The documents from early to late 1956 record the events as they played out for the strikers in a time when shearers stuck together, and paid a special levy into a strike fund to support those shearers who could not find work on the ‘old’ rates.

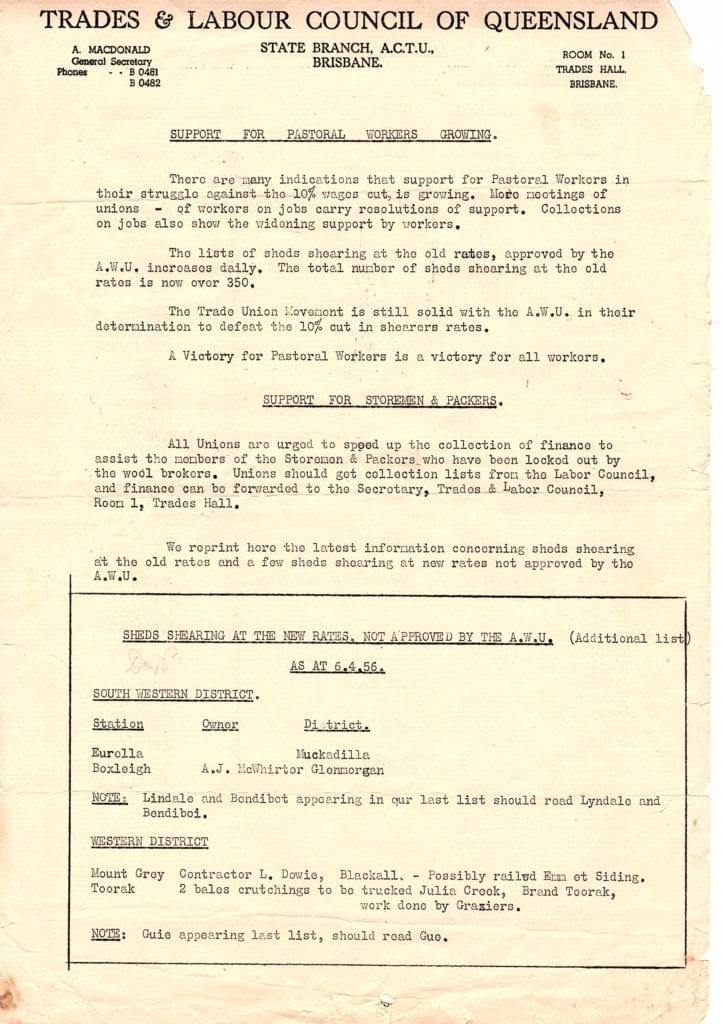

They include lists of sheds where sheep were being shorn at the ‘new’ rates – ‘black wool’ – not approved by the union.

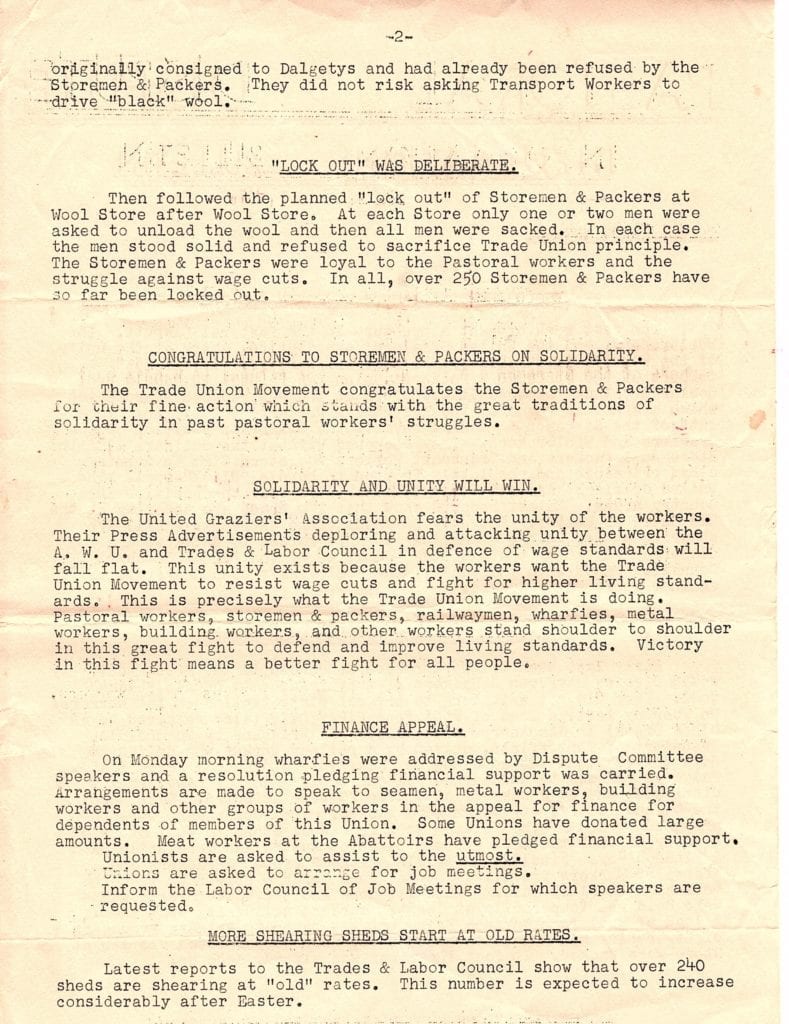

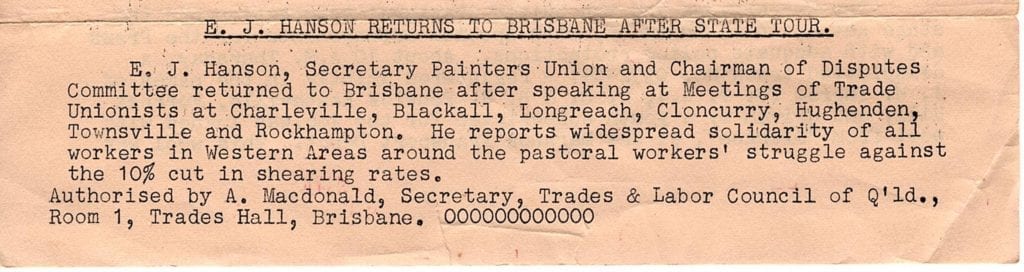

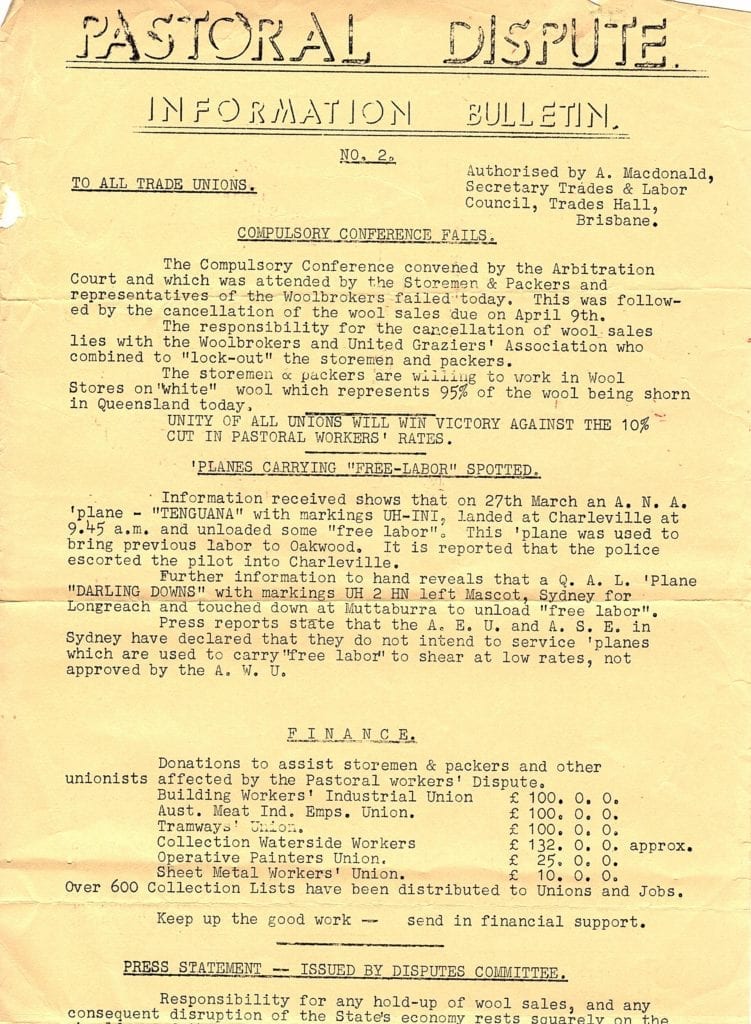

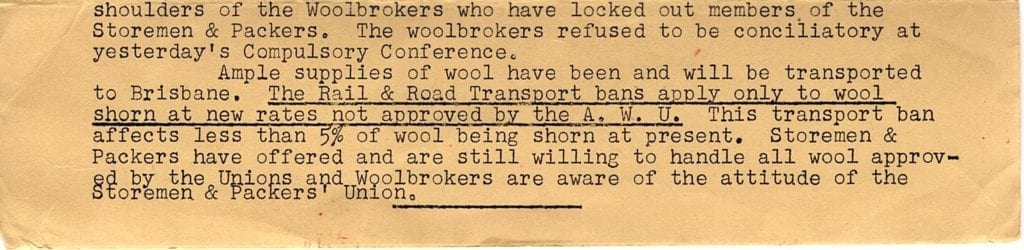

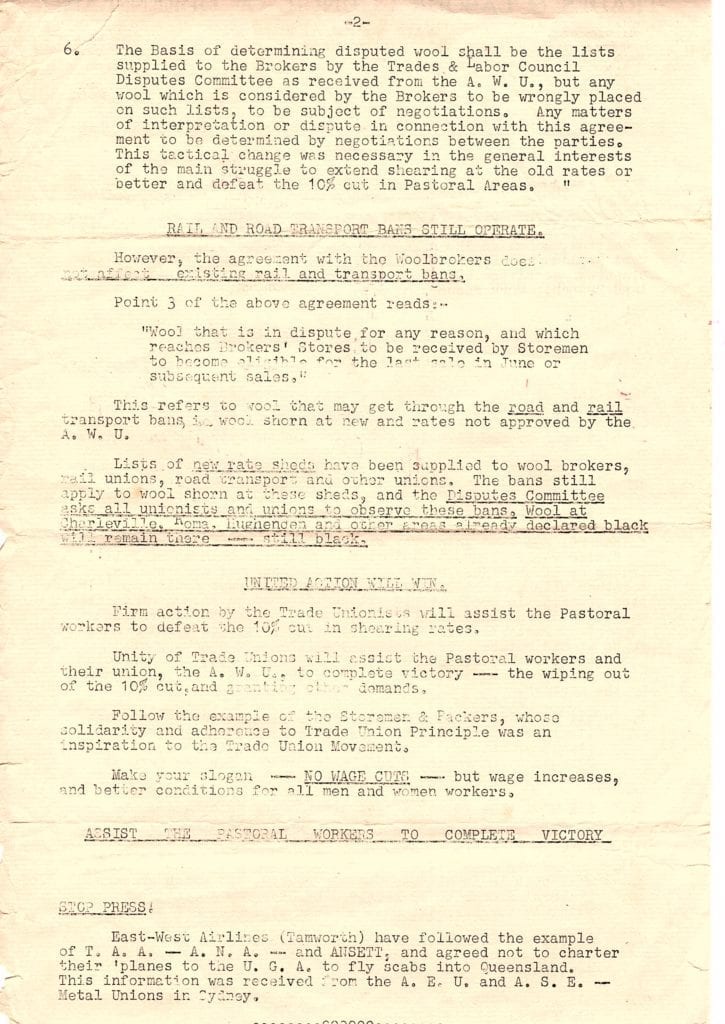

Pastoral Dispute Information Bulletins were issued by the Secretary of the Trades & Labour Council throughout the strike. They kept trade unionists appraised of developments in the overall activity across the state.

It was the time of telegrams

Contract

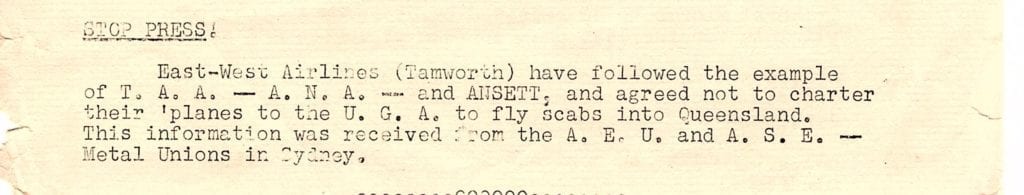

The Bulletins were used to pass on ‘good news’. An example can be found at the end of one Bulletin – airlines at the time agreed not to charter their planes to fly non-union labour into Queensland.

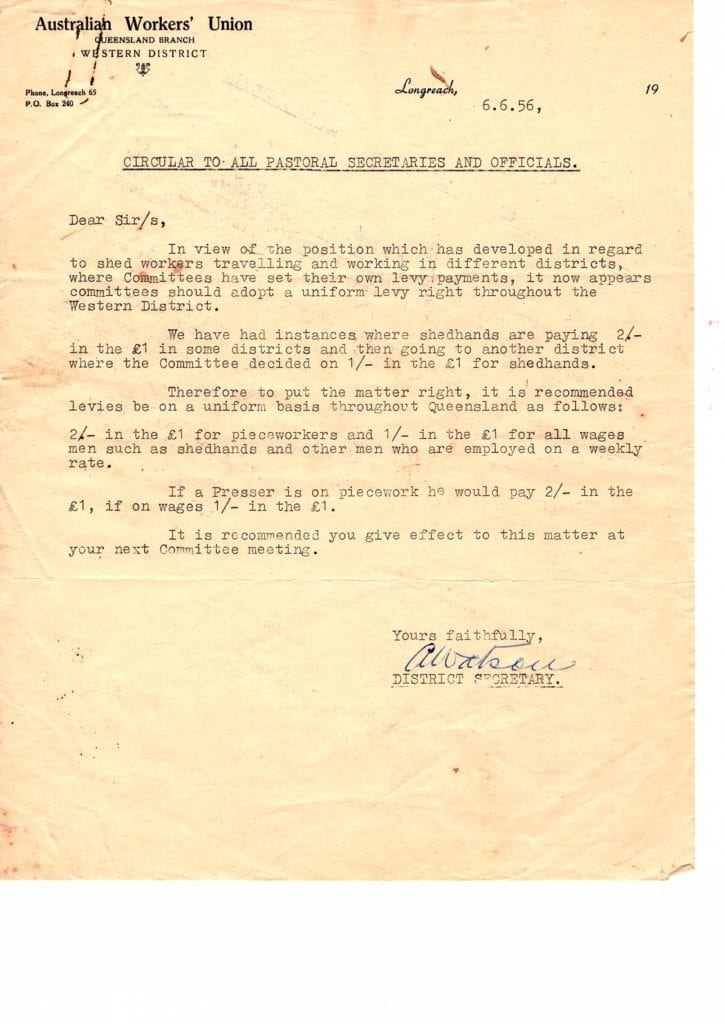

By June, the local Western committee had made a determination on the levy to be paid by shearers. Payment of the levy entitled them to be able to work at the ‘old’ rate in the sheds willing to pay at that rate.

There are examples of how this was monitored, but I have not included these documents as they name individuals.

They show that some shearers, although they registered, did not pay the levy. Once realised, these men had to be tracked by the AWU, and encouraged to pay up in solidarity. They couldn’t work at the ‘old rate’ without paying it. The ‘new’ rate was less.

Relief Monies Collected and Distributed

Finally in October 1956, the Arbitration Court brought the shearing rate into line with a federal award (a little less than the 10% reduction) and the strike ended in compromise.

Wool was still valuable, so much so that even skins were of value but there was no longer need to scour wool prior to sale and by 1957 Westbourne Scour, which had peaked its output in 1917 (with 15,000 scoured bales out from 20,000 greasy bales in) found it uneconomic to carry on. The property was sold to M. I. and M. K. Nicholson, who disposed of the machinery for scrap and most of the buildings for removal.