Source: St. Pierrre, John. Barcaldine and the 1891 Shearers' Strike. Unpublished manuscript, 1982.

THE BARCALDINE STORY - THE SHEARERS’ STRIKE 1891

In its history, Australia has only seen two armed insurrections between white settlers and government-backed forces – the Eureka revolt of 1854 and the Queensland Shearers’ Strike of 1891.

Recognised as one of Australia’s first major industrial disputes, the Shearers’ Strike occurred during the overseas-induced depression of the 1890s. Economic instability overseas impacted on falling wool prices in Australia, creating tension between the shearers and the pastoralists who proposed a reduction to the shearers’ wages, which then stood at £1 per hundred sheep shorn.

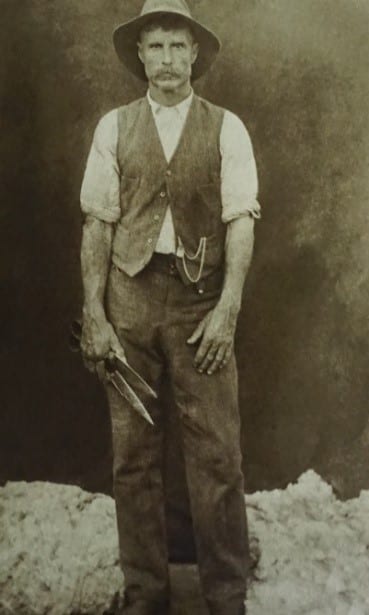

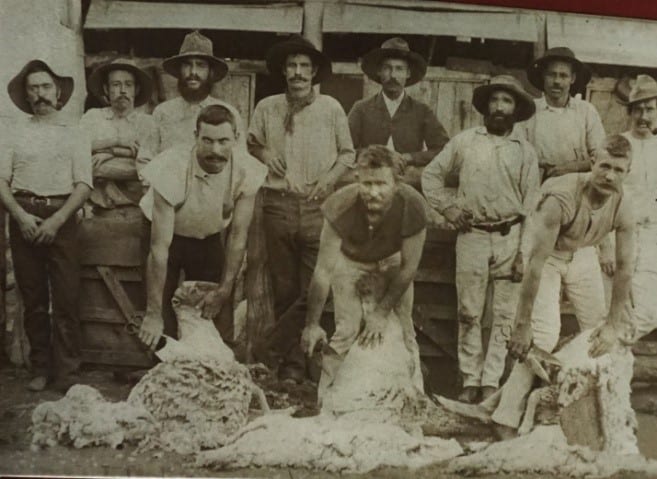

The first pastoralists in Australia had assigned convicts for their employees – paid no wages, and rations according to Government regulation. These men were mainly employed as bushworkers – shepherds and stockmen. If their labour proved unsatisfactory they were sent back to the road gangs in the various settlements. As time moved on, many of them became free, and were then able to bargain for better working conditions. They were paid very meagre wages but better than when they were working in bondage. Every claim they made for improved conditions was resisted, they were accused of being greedy and indolent, and wanting luxuries such as tea and sugar. When the gold rushes ended, there were large numbers of unemployed in the country and cities, and an industrial war began. There was no organisation among the bushworkers and they were at the mercy of the employers for the conditions of their livelihood. Disputes started between pastoralists and workers over shearing rates, with a proviso to reduce the shearing rate if the job was not done satisfactorily to the employer. Although jobs might be held up, in the end the employer usually won. During this period, once the shearer or shed hand signed the agreement, until the job was finished, he could not leave without being penalised; but he could be sacked without redress. Rations had to be bought from the station store at the owner’s prices. The accommodation was draughty huts usually built of slabs without any windows, with a bare earth floor, rough board bunks with neither mattress nor even straw, built in tiers around the walls with a dining table down the centre, and the fireplace at one end. The cook was engaged, and wages paid by the shearers. Sanitation was usually unknown, or of a very primitive nature, often flowing into the only water source. On average, shearers travelled up to 300 miles between sheds, mostly on foot and bicycles.

When shearers began to dispute the conditions of their work, some employers compiled a black list of shearers and labourers to exclude the marked men from employment. The blacklisted men countered by changing their names.

This state of affairs continued for many years, without change, until the bushworkers noticed that the miners had formed themselves into organisations to bargain collectively with their employers to do something to improve their working conditions. Consequently, in 1886, the secretary of the Amalgamated Miners’ Association in Ballarat was approached to work for shearers – the shearers’ rates were then threatened with a reduction of 2/6 per 100 sheep to 15/6 per 100. The Amalgamated Shearers’ Union was formed from a meeting of 40 shearers in Ballarat, developing into the Australian Workers’ Union.

The formation of a shearers’ union was a challenge to the pastoralist, and the industrial fight became increasingly bitter, with sporadic strikes occurring all over the country mainly as a reaction to the employment of free labour (non-unionised workers).

Barcaldine was only five years old when it became the scene of the major confrontation between bush workers and pastoralists. Pastoral leases taken up in the early 1860s brought settlers to the Barcaldine area, then known as Barcaldine Downs. Settlement of the township began in 1886 with the advancing rail line from Rockhampton.

The main buildings of the embryonic town were made at various termini of the rail line construction, with some moving four or five times before coming to rest 358 miles west of Rockhampton. With these buildings came their owners and managers, much travelled businessmen, anxious for a permanent home. Navvies, lengthsmen, plate layers and general hands were employed on the line. Carriers and coachmen ploughed the dusty tracks linking the railway to the pastoral areas it served. The railway line eventually took over much of the livelihood of the teamsters. For several weeks during the shearing season, large numbers of extra men were employed as shearers and shed hands. These men were nomads, carrying their swags from one place of work to another, plagued by fever and scurvy, and sometimes living only on fauna they caught or shot.

The Start of the Conflict

Near the Barcaldine railway station, under a spreading gum tree, meetings began to take place and the idea of forming a union was born. The Central Queensland Carriers’ Union was launched in February 1887 at the same time as the Queensland Shearers’ Union formed after a public meeting in Blackall. The Central Queensland Labourers’ Union became registered in early 1889. Support rapidly grew.

In April 1889, alarmed by the power unions were assuming, the pastoralists gathered in Barcaldine and formed a Pastoral Employers Association. They adopted a platform and a policy of collectively resisting anything that was put forward by the shearers’ union. In 1890, there was a good deal of trouble between the two forces.

1890 On 12 July, the Amalgamated Shearers’ Union manifested ‘none but union agreements’, essentially a ‘closed shop’ to protect their right to uniform wages at set rates achieved through collective bargaining. In November 1890, the Queensland Pastoral Employers Association set out their ‘Freedom of Contract’ based on individual contracts as the mechanism for enforcing an employer’s right to set wages, free of union rules. The wages were reduced by amounts varying from 5/- to 15/-. The minimum rate previous to 1891 was 30/- per week and keep. The unions refused to accept the contract.

These events set the scene for the conflict that erupted in January-February 1891.

The Clash

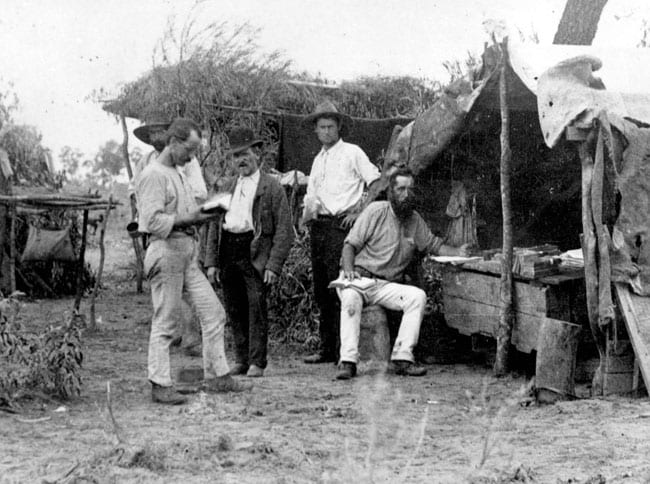

1891 On 5 January, the shearers’ unions (Queensland Shearers’ Union and Queensland Labourers’ Union) gathered in Barcaldine and set up strike committee headquarters in Ash Street. Strike camps were formed in different parts of Queensland – from Cloncurry to the NSW border – with large camps in Barcaldine and Clermont.

The strike was called.

Discussions between unions and employers continued but broke down.

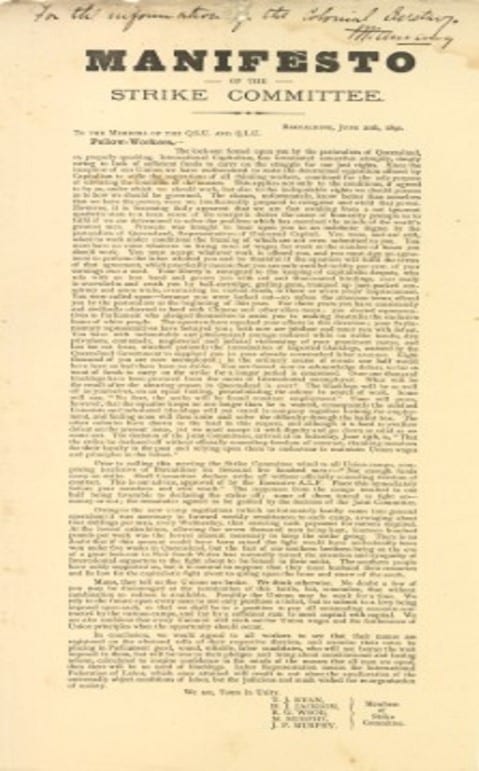

On 2 February, a union manifesto to ‘take such action as will best conserve our interests and frustrate the attempts of organised capitalism to crush unionism and reduce wages in this district’ was issued to shearers and rouseabouts.

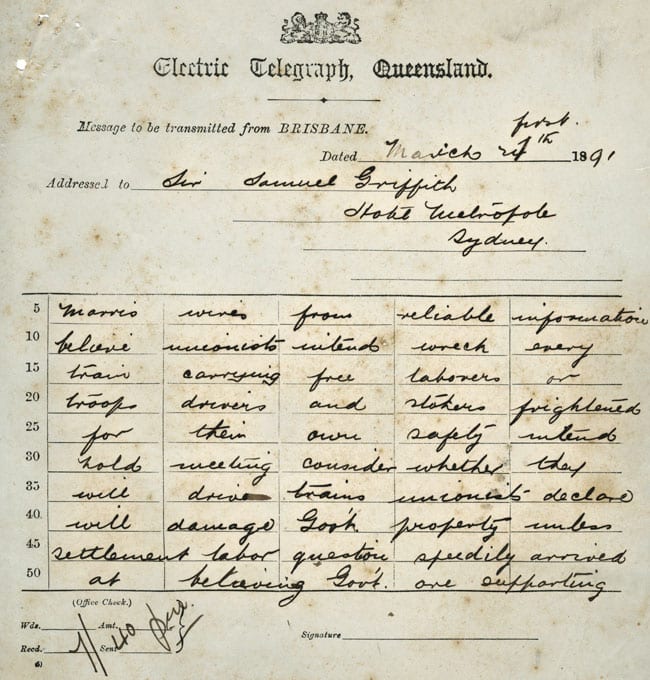

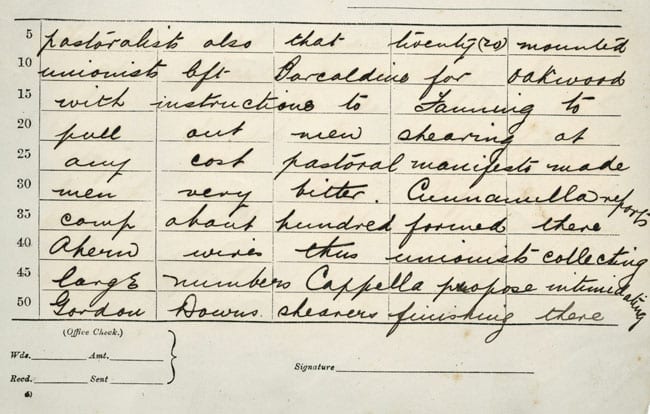

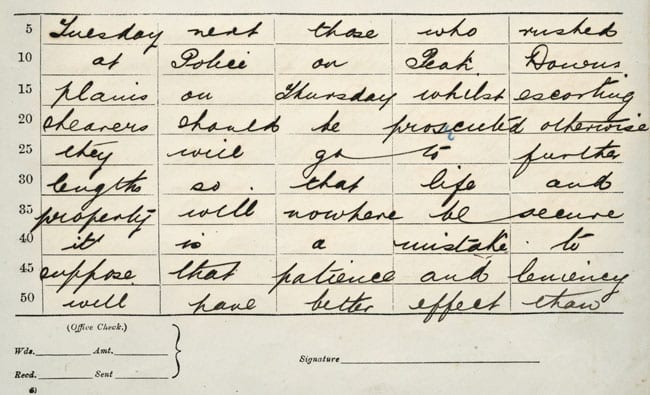

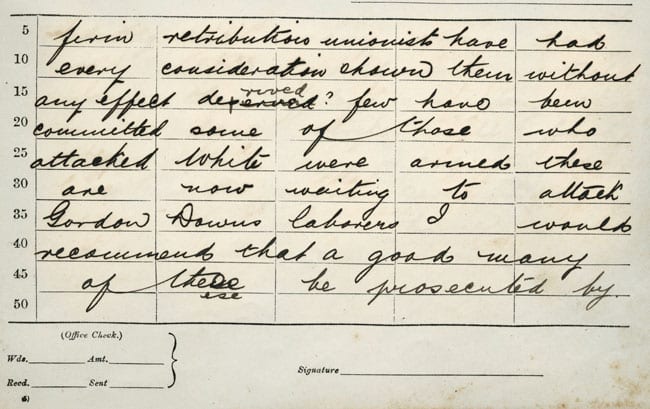

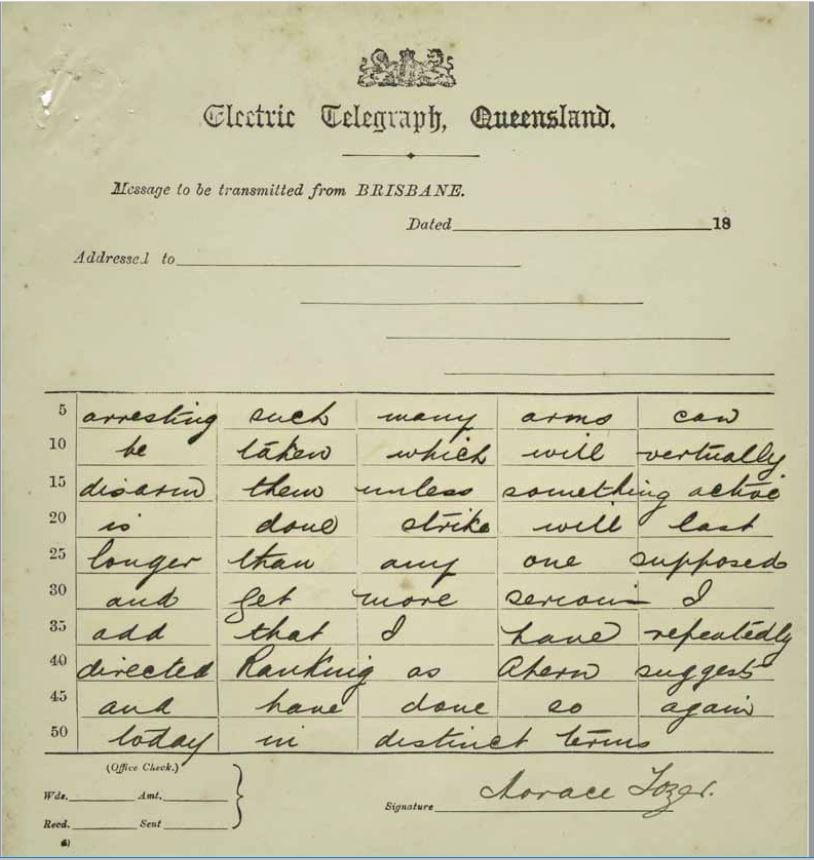

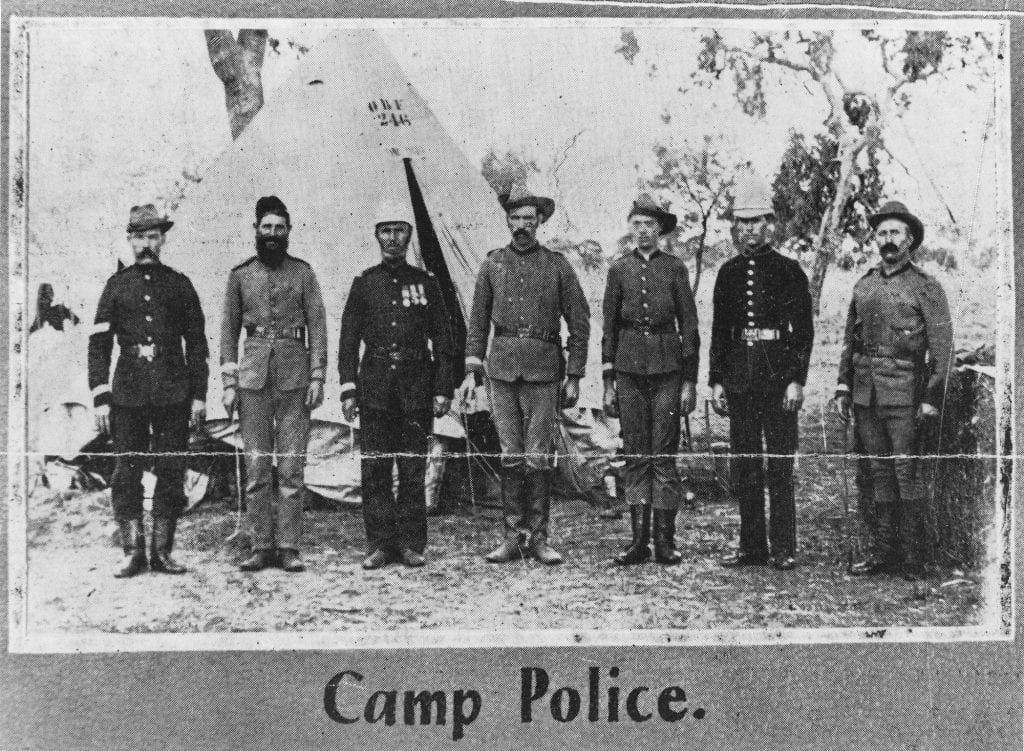

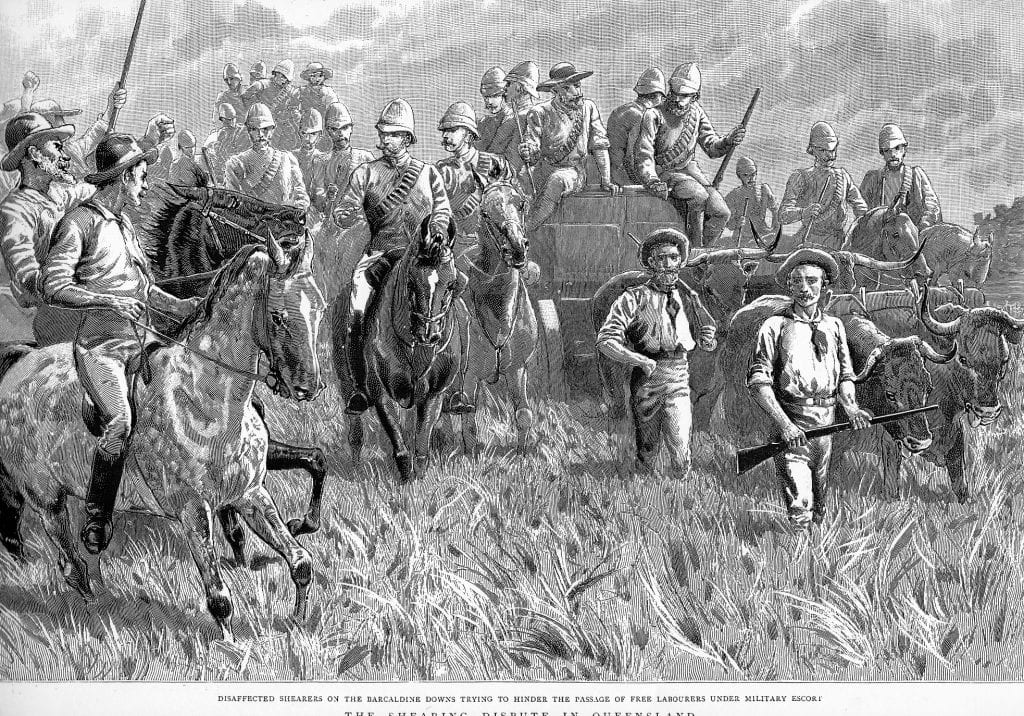

In response, the following week, the pastoralists arranged for free labour (called ‘scabs’ by the unionists) from Victoria by train to travel to Clermont and Barcaldine, protected by Queensland Government-provided police and reinforced by militia and volunteers. Several incidents occurred around Clermont in attempts by the strikers to intercept the free labour including attempts to side track the train and uncouple the carriages, and to destroy a railway bridge. Not all the pastoralist’s took part in the dispute, with some notable landowners refusing to engage in the hostilities.

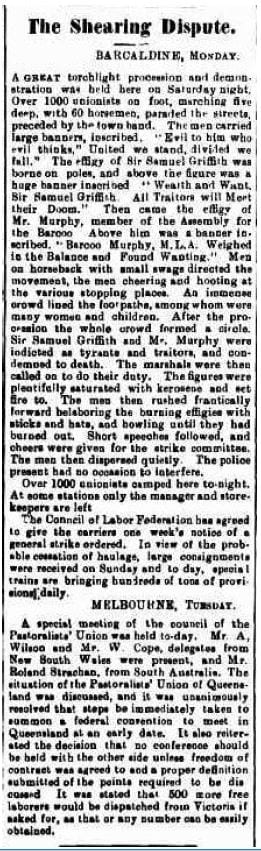

During the latter part of February, the dispute developed very rapidly, both in the affected areas and in the headlines of the Press. There was, however, evidence of tolerance on both sides, and any shots that were fired during the strike were accidental, and no one was injured. Torchlight processions with large banners began in the main street of Barcaldine, with over 1000 men on foot, 60 horse men and a brass band taking part. Locals lined the street outside the hotels to call out encouragement or otherwise, and to cheer the burning of effigies.

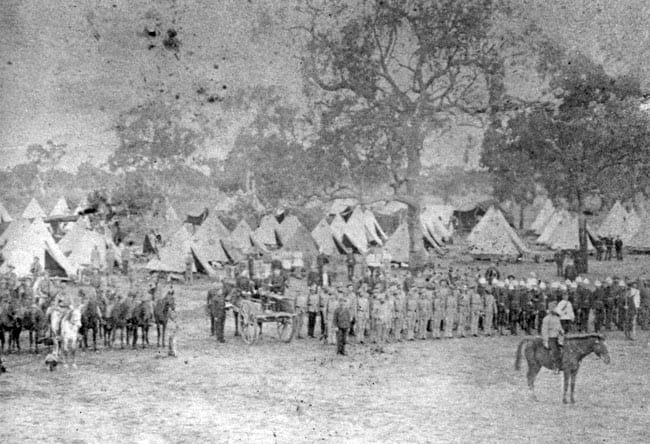

On 10 March almost 1500 unionists met two dozen police and blocked the platform at Barcaldine railway station. No shots were fired. Tension continued to build as military personnel arrived in Barcaldine by train, and a military camp was set up near the court house. Altogether about 1,000 military personnel were sent out to be scattered in camps all over the western districts of Queensland.

Military posts had also been set up at Muttaburra, Isisford, Aramac and Blackall.

The Authorities

The Strikers

Torchlight Procession

Thursday 26 February – Saturday 28 February 1891

…the news was passed around in Barcaldine that the Unionists were planning a torchlight procession for the following Saturday night. On the Friday the news was confirmed by placards posted in the town announcing a grand demonstration and a torchlight procession of horsemen and footmen. It was estimated that eight hundred would take part. The local brass band had been engaged, but members who were in the police force had declined to play. Later in the day the Government proclamation was posted throughout the town and there was some speculation that this might stop any demonstrations. The police weren’t very concerned at this stage and did not anticipate any disturbance. Some of the local Chinese population were concerned, however, and appealed to the Police Magistrate that day for protection.

The evening of Saturday, 28 February brought the torchlight procession through the streets of Barcaldine amid scenes that attracted the interest of the townsfolk. Over a thousand Unionist footmen, marching five abreast and accompanied by sixty horsemen, paraded the streets led by the town band. The men near the head of the procession carried a banner which read, “Evil to him who evil thinks”. Further down the line an effigy of the Premier, Sir Samuel Griffith, was borne on poles. Above the effigy was a huge banner, “Wealth and Want. Sir Samuel Griffith and all traitors will meet their doom.” Then came an effigy of Mr. Murphy, the member for Barcoo. The banner above him was inscribed, “Barcoo M.L.A., weighed in the balance and found wanting.” The men on horseback carried small flags and rode about directing the cheering and the hooting at various stopping points. An immense crowd, including women and children lined the footpaths to watch the procession pass by. Eventually the procession halted and the whole crowd formed a circle while the effigies of Griffith and Murphy were indicted as tyrants and traitors and condemned to death. The marshals were called to do their duty and the figures were saturated in kerosene and set on fire. Some of the men then rushed forward belabouring the burning effigies with sticks and hats. Cheers were given for the “Sydney Bulletin” and for the strike committee. The police were present in the streets throughout the evening but had no cause to intervene. Eventually the men dispersed quietly, and the townsfolk returned to their homes.

Excerpt from Barcaldine and the 1891 Shearers’ Strike (St. Pierre, John. 1982)

The Arrests

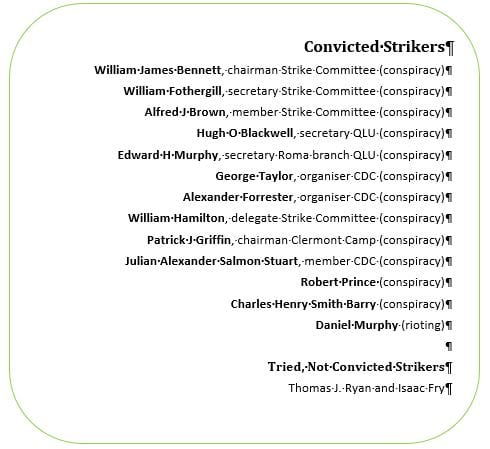

From the 23-25 March the alleged strike leaders were arrested in the Clermont district and the strike committee was arrested at Barcaldine. There was a preliminary hearing in the Barcaldine local court before they were sent for trial in Rockhampton on charges of conspiracy.

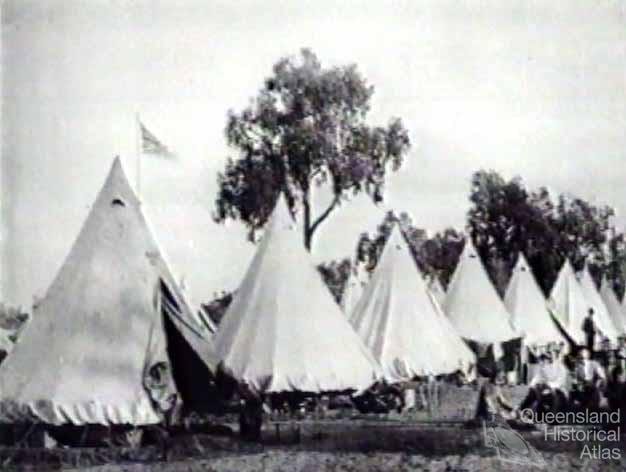

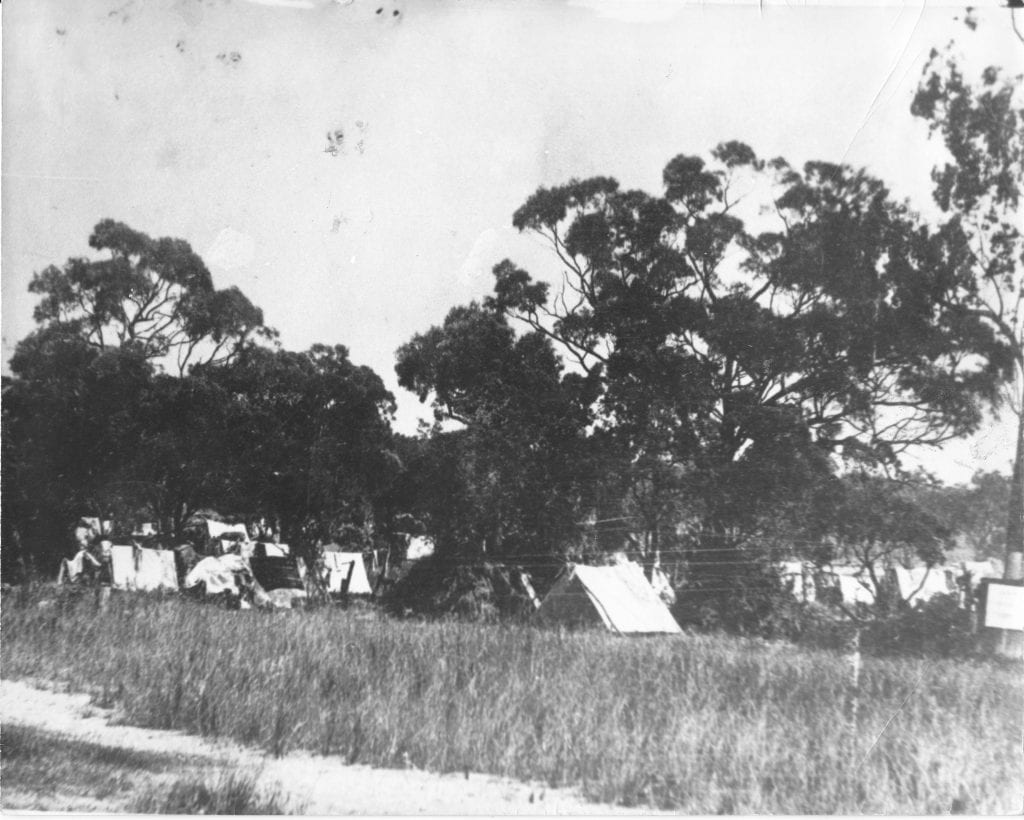

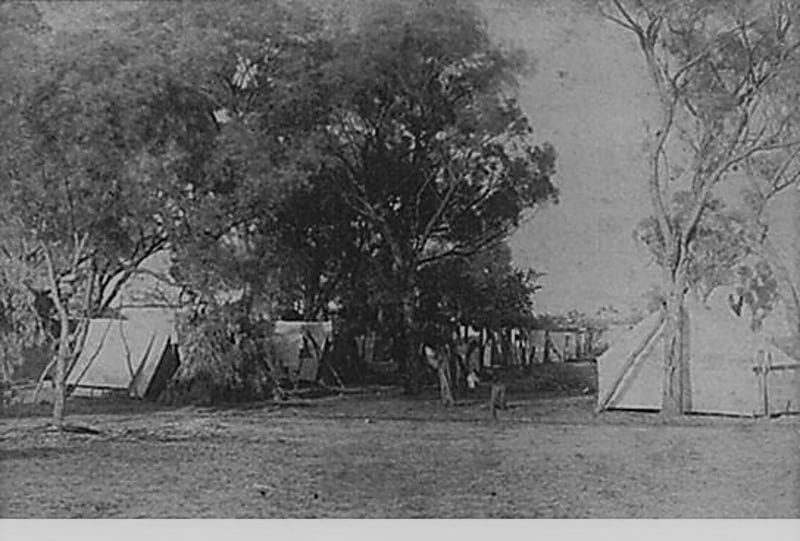

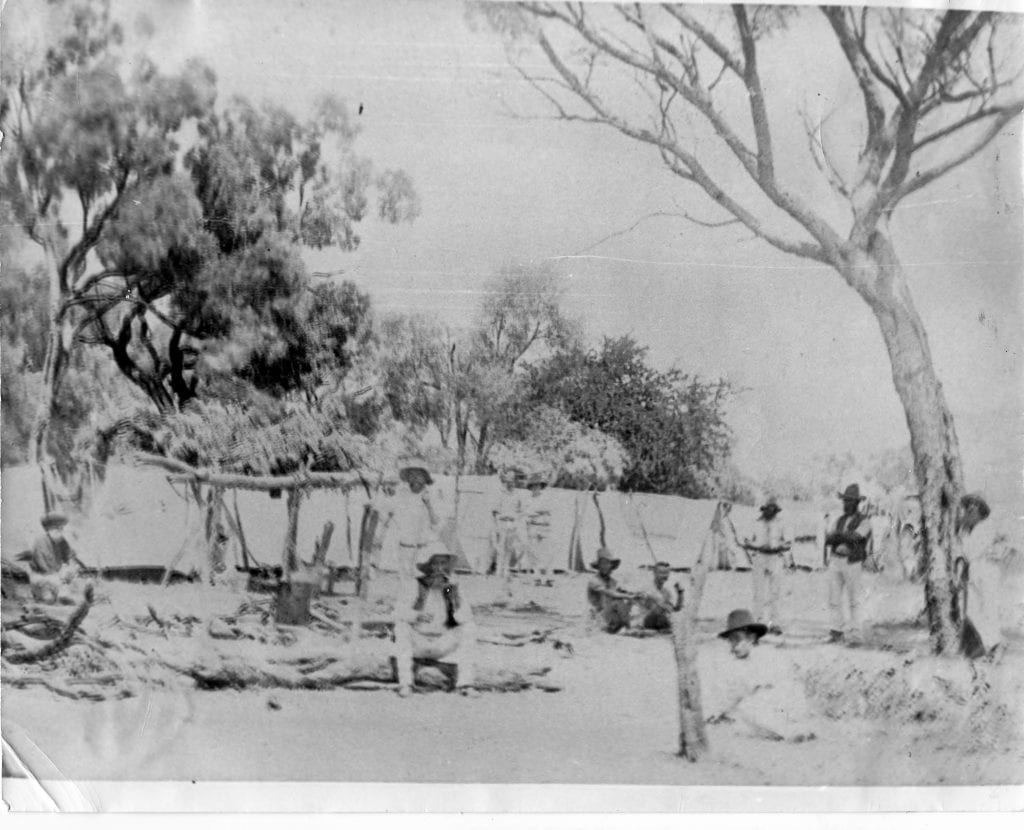

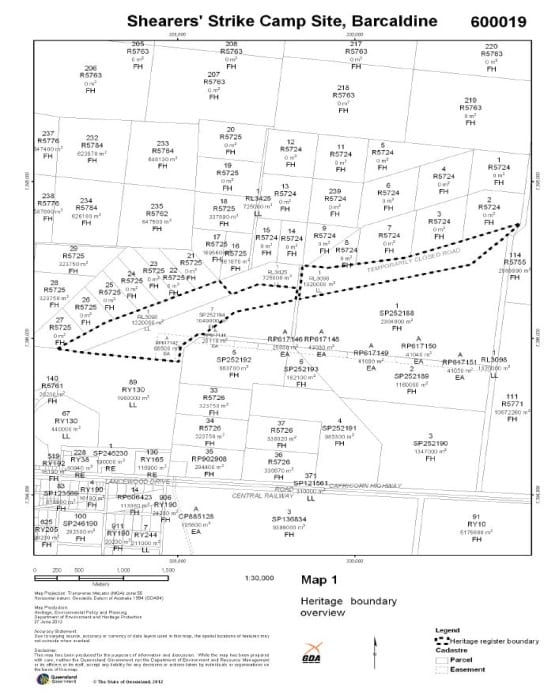

In April, it was estimated there were over 9000 men on strike and about 8000 living in strike camps from the Gulf of Carpentaria to the New South Wales border. The main strike camp in Barcaldine, on the southern bank of Lagoon Creek is said to have held up to 1000 strikers, some of whom were accompanied by their families.

It is contended that, in May, at least 3000 striking shearers marched under the Eureka Flag to put forward their protests against poor working conditions and low wages beneath the branches of the spreading gum tree outside the Barcaldine railway station (now known as the Tree of Knowledge).

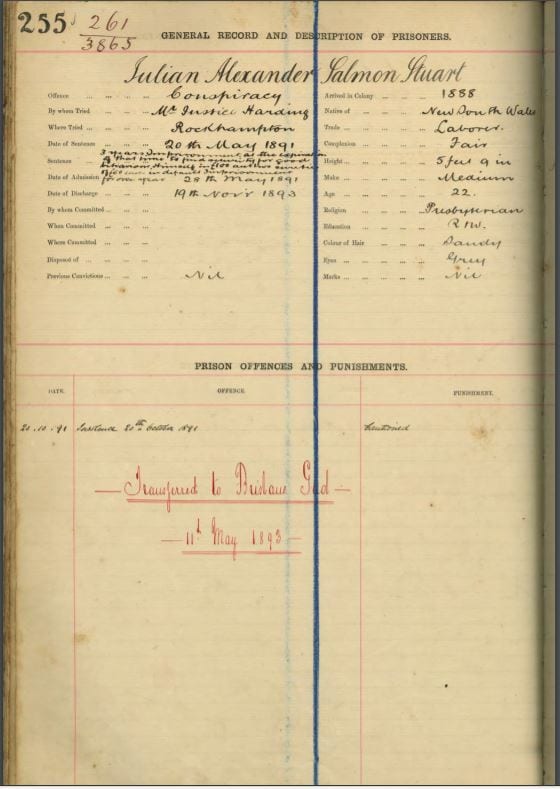

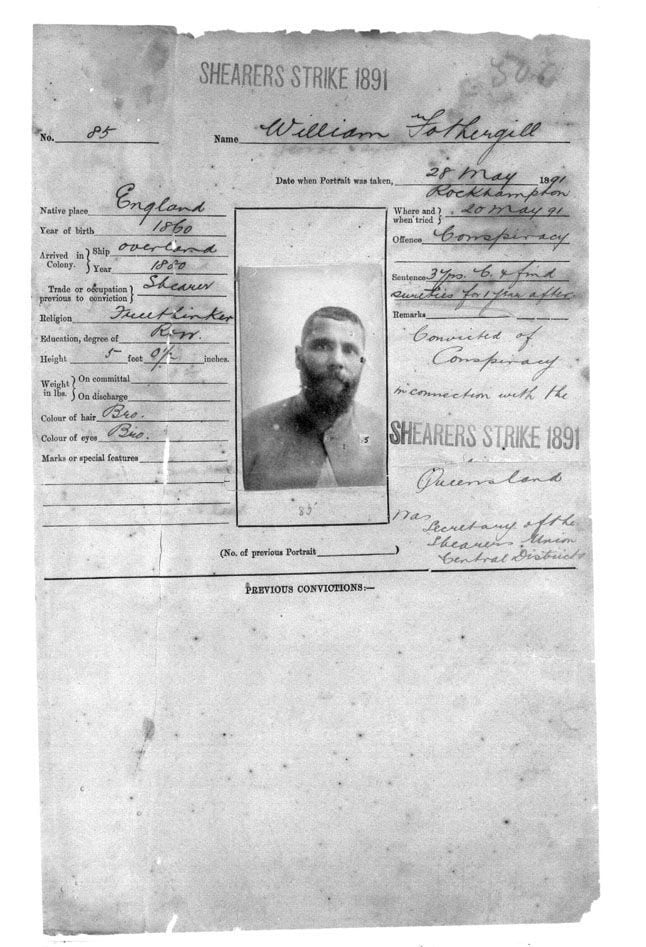

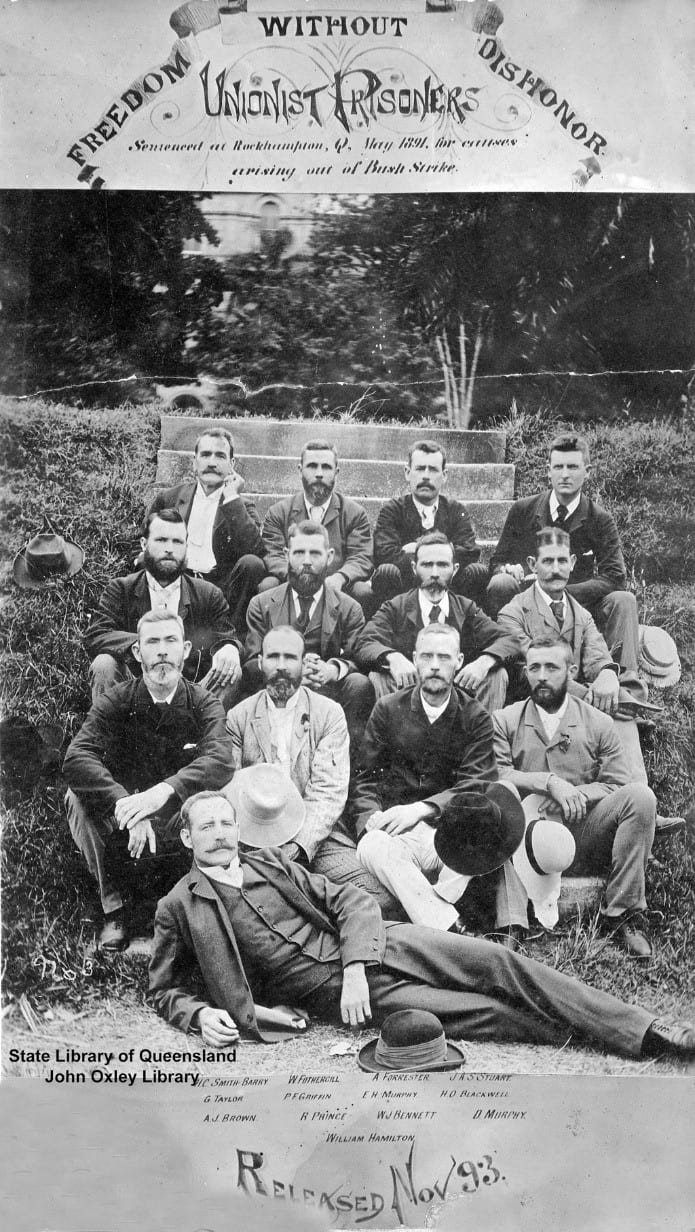

On 20 May, all but two of the alleged conspirators were sentenced to three years imprisonment with hard labour on St Helena Island in Moreton Bay. The full sentence was served by the unionists despite an appeal to the Government for their release. The Government did express its willingness to release them, but on the proviso that they themselves petitioned for clemency, and admitted that their actions had been unlawful and unjustified. They all refused.

The conviction of the strikers was a fatal blow to the unionist cause, but until the situation was recognised, the strike continued.

By mid-June, however, with the leaders in jail, the strike began to lose direction. On-or-about the week of 18 June it was called off. By that time, free labour was being employed everywhere, the sheep were shorn, and wool was transported to railway stations.

In August, a two-day conference between representatives of shearers and pastoralists worked out an uneasy peace, with pastoralists agreeing to recognise the union but reserving the right to employ non-union labour.

The Queensland shearers, leaderless, defeated, out of funds, and camping in incessant rain, went back to work largely on the pastoralists’ terms. About all the strikers got out of the dispute was experience, but the upheaval gave an impetus to political Labour.

The Aftermath

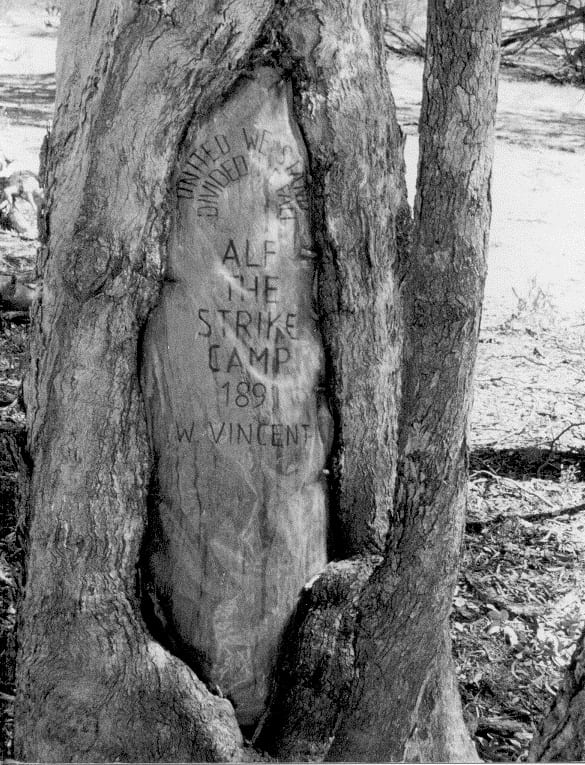

Workers took a keen interest in politics, but it was a difficult task to gain the right to vote. Many workers were denied the right to vote under the franchise in those days. The Labour movement’s understanding that social change could be achieved through parliamentary power has its roots in the shearers’ struggles of the 1890s, and its move to the political arena is symbolised in Barcaldine by the Tree of Knowledge, where an armed uprising and loss of life were avoided, and where unions met in 1892 to form the ‘Workers Political Party’ which became the Australian Labour Party (ALP) – the oldest political party in Australia prior to the first sitting of the Commonwealth Parliament in 1901.

In March, 1892, T. J. Ryan was elected to Parliament as the representative for Barcoo, and was the first endorsed Labor member elected to the Queensland Parliament. He did not seek re-election when his term expired, but returned to the west. T. J. Ryan was a union secretary and was one of those jailed in 1891 during the pastoral strike. Another endorsed Labor candidate, G. J. Hall, was elected in June of the same year. Another T. J. Ryan became the Premier of Queensland, and died in Barcaldine.

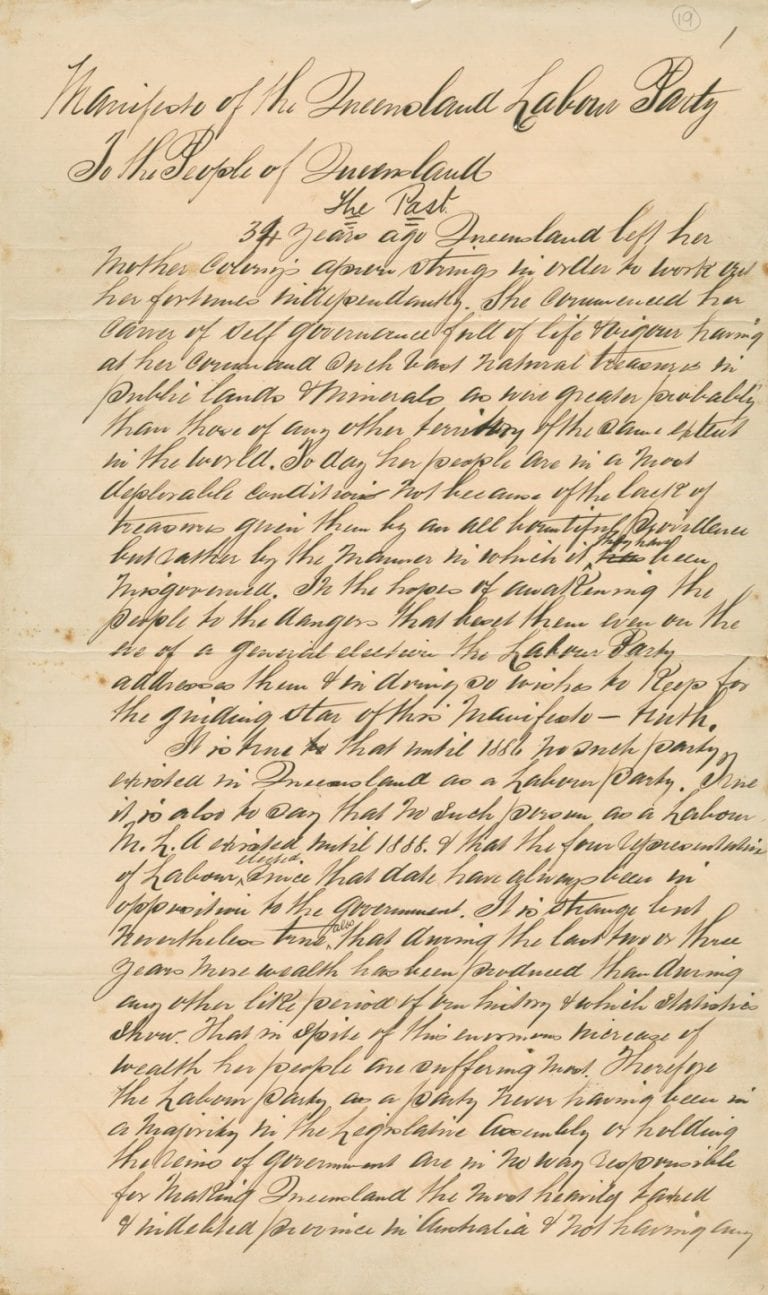

The Manifesto of the Queensland Labour Party (written by Charles Seymour and dated 9 September 1892) was an important link in the chain of actions and events in Queensland in 1891. In 1899 Queensland elected the first Labour Government in the world. The ALP adopted the formal name ‘Australian Labour Party’ in 1908 but changed the spelling to ‘Labor’ in 1912.

Since those early days in Barcaldine of the struggle for workers’ rights and conditions, many more unionists and ‘true believers’ have continued to have faith in the capacity of Labor to capture control of the political system by constitutional means and to use parliamentary power as an instrument of social change.

Since 2007, the memorial to The Tree of Knowledge has become a powerful symbol of the endurance of workers’ rights, now included on the prestigious UNESCO list of sites of world significance.

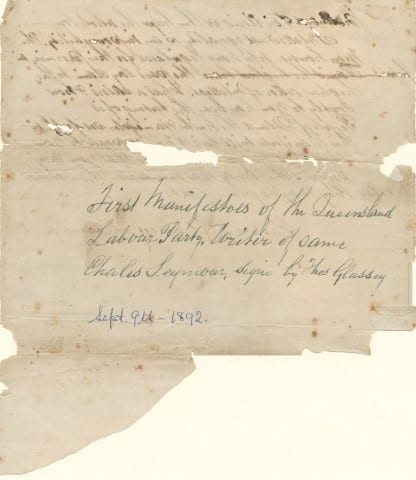

Heritage Listing - Strike Camp

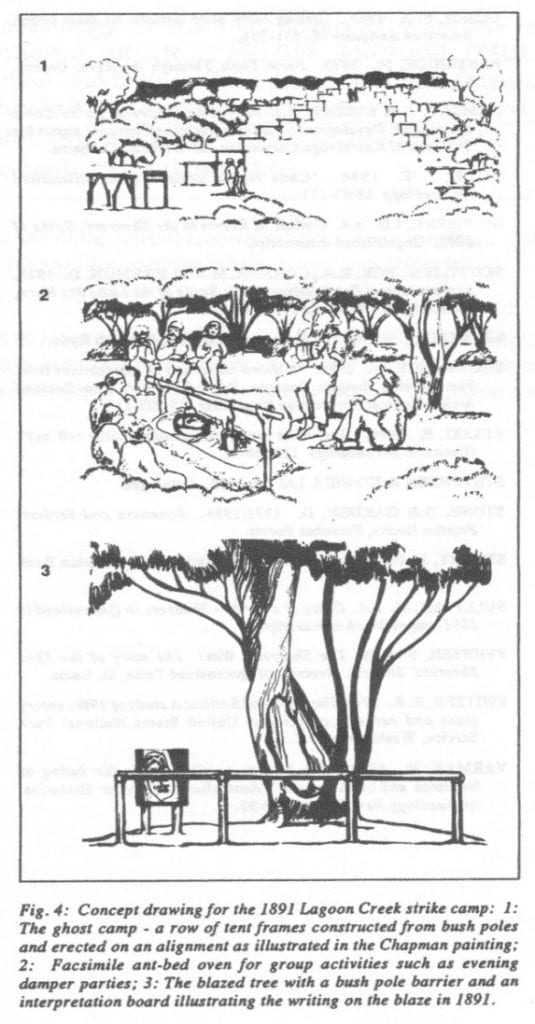

In July 1989 archaeological excavations and historical research was carried out at Lagoon Creek and at the Alice River, near Barcaldine in west central Queensland in relation to the 1891 shearers’ strike camp at Barcaldine. This work when matched with recently discovered pictorial information confirmed that Lagoon Creek was indeed the location of the main strike camp. Additional archaeological research brought to light a number of artefacts, both portable and landscape features. Once the fabric of the site was defined and the significance of the place established it proved possible to suggest that the interpretation plan focus upon a low-key presentation with reconstructions being limited to a ghost camp, or a series of tent frameworks evocative of the place at its time of abandonment. The

DID YOU KNOW...

Henry Lawson’s well-known poem, ‘Freedom on the Wallaby’ was written as comment on the 1891 shearers’ strike.

Major southern newspapers sent ‘war correspondents’ to report daily on the shearers’ strike.

The strike committee office was moved on wheels from Ash Street to a position behind Lennon’s Railway Hotel and became the hotel kitchen until it burned down with the hotel in the 1927 or 1929 fire.

Some of the arrested strike leaders went on to play significant roles in public life after being released from prison.

William Hamilton won the state seat of Gregory for Labor in 1899, and subsequently became President of the Queensland Legislative Council. He died in 1920.

William Fothergill carried on a baker’s business in Barcaldine; became a member of various committees, and was Barcaldine Shire Chairman from 1919-1920. He is buried in the Barcaldine cemetery.

George Taylor was appointed Speaker of the Western Australian Legislative Assembly.

T J Ryan became the first endorsed Labor member of the Queensland Legislative Assembly in 1892. By a remarkable coincidence the shearer and union secretary T. J. Ryan referred to above, Member for Barcoo, was followed in the same electorate in 1909 by another T. J. Ryan (Thomas Joseph) who became Labor Premier of Queensland in 1915, and Deputy Leader of the Federal Labor Party in 1920 – he died in Barcaldine on 1 August 1921, aged 45, and his body returned to Brisbane for interment in the Toowong Cemetery. READ MORE ABOUT THOMAS JOSEPH RYAN

Julian Stuart became a writer of note and eventually editor of the Westralian Worker.