World War I

News of the war in 1914 was met by an immediate show of loyalty. The streets were too dusty for a procession but the flags were flown, the band played, and a large crowd gathered at the shire hall for speeches and fund raising. £979.9.3 plus 750 fat sheep were pledged on the first night.

Within a month, the first men left for the front, ‘sturdy, bronzed, robust young fellows’, according to the Champion, and a ‘credit to the district’. There was a farewell function at the Shakespeare, a procession, and the band playing by the Tree of Knowledge as they steamed away on their fateful journey to the Dardanelles, off to defend a ‘homeland’ most had never seen.

There were other departures almost every week, fund raising committees worked to support the cause, and social life almost ceased.

News from the war zone came through slowly and was always slanted towards optimism. On 8 May 1915, the Champion reported,

‘It is now known that Australians are in the Expeditionary Force under Sir Ian Hamilton on the soil of Turkey in the Gallipoli Peninsular. The landing was effected without accident . . . They are advancing towards Constantinople . . . The Turks are in a position of abject fright’.

As the truth became known, pride tempered grief. Those who had lost sons bore their tragedy with the help of public approbation.

In November 1918 ringing of the school, fire, and church bells was mistaken at first for a fire alarm as they peeled out about 11 pm. As news of peace spread, people crowded the streets banging kerosene tins and clanging bullock bells. Several days of celebration followed. Schools closed, there was a procession and an effigy of the Kaiser burned on a bonfire. At a more solemn level, there were thanksgiving church services.

There were 13 Barcaldine enlistees in the first contingent. Graham, Moore and Clarke did not return.

J. West

T. W. Lewis

G. W. Appleyard

J. Monoghan

J. G. Geshensky

J. C. Sain

C. D. Gray

C. D. Crouch

H. E. Dennett

H. Graham

A. Moreau

S. W. Moore

A. Clarke

In September 1915, J. G. Miller of Mildura, Barcaldine, donated £10.10.0 for the first western Queenslander to win the Victoria Cross. The money, augmented by two other donations of £10.10.0 was presented to Lieutenant E. T. Towner of Purtora, Yalleroi, in December 1919. Towner won a D.S.O. and M.C. and the V.C. for his war service, the latter at Mont St. Quentin for capture of a German gun which he turned on the enemy.

By the end of 1915, the newspaper began to print letters from the front. Lieutenant M. Lyons wrote from France that he had spent 16 weeks in bed after being dragged from the trenches and left with a pile of the dead. That was a bad experience but he was ‘all right now‘. He wrote, ‘When I get my wooden leg I’ll be able to carry on much the same as ever . . . my stump will trouble me less than the consciences of those blighters left behind should trouble them‘.

Anzac Day

Barcaldine organisers were unsure how to celebrate the first Anzac Day. Back then, it didn’t seem right to treat it as a holiday.

In time, church services, closed hotels and a return to work in the afternoon became the custom.

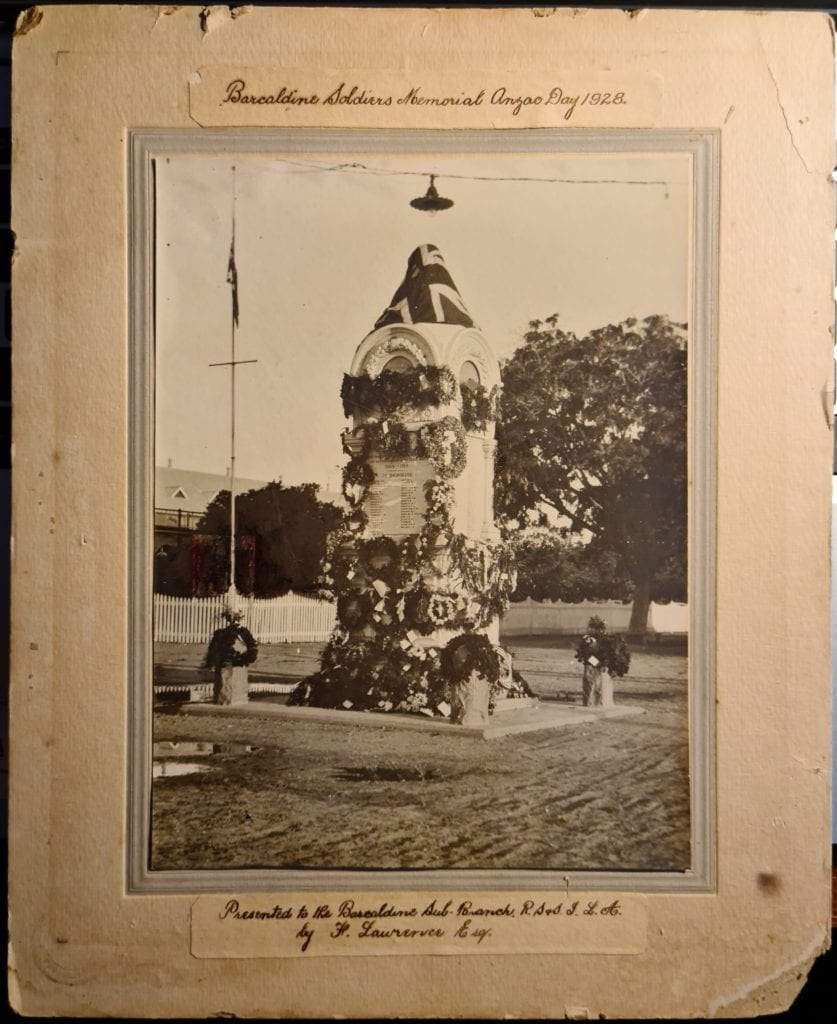

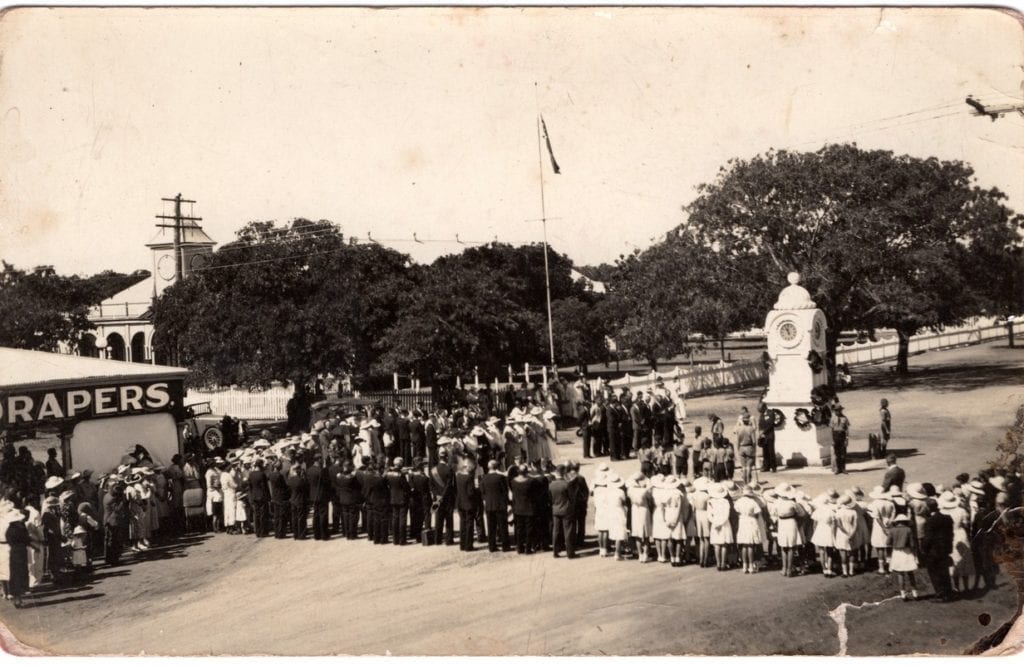

The Memorial Clock was built on the intersection of Ash and Beech streets in 1924. Anzac Day processions were then held, ending at the Clock.

Anzac Day commemorations are now held in almost every town in Australia on 25 March.

World War II

Outbreak of war in the Pacific in 1942 brought traumatic and unforgettable events to Barcaldine. Amenities that had been barely adequate suddenly had to serve a dramatic influx of population.

Girls from two boarding schools and families from coastal towns had to be accommodated.

Urgent plans were made for reception of evacuees. A survey found private accommodation for 75, another 215 could be housed in public buildings and hotels could take 100 more. Some would be taken by country families and beds could be obtained from shearing sheds.

- Extra food storage was arranged, mainly in the show pavilion.

- A Volunteer Defence Corp formed and trenches were dug at all institutions to serve as air raid shelters.

- A roster was drawn up for ‘spotting’ of possible enemy aircraft, the deck of the Shire Hall used as a lookout.

- Waste paper, rubber and metal were collected and a bin in Oak Street was reported to contain, among other things, six old band instruments – relics of the shearers’ strike days – to be carted away for the war effort.

- The hospital was in bad condition and the town had no ambulance, so hasty meetings arranged for trained nurses in the community to stand by if needed and for stretchers to be set on rollers for transport of patients; surgical supplies were distributed around the town.

- A War Damage committee formed to cope should the worst happen, planning to use the Ash Street bore if the power house was bombed.

- Councillors were informed that a Local Authority election, due in 1942, would not be held. Existing members had to carry on.

When news of peace reached Barcaldine on the morning of 15 August 1945, residents gathered at the war memorial for a short service and observance of one minute’s silence.

A procession of celebration at 2 pm was made up of anything that moved – lorries, cars, horses, bikes, even a Chinaman, Charlie Gunbow, pushed in a wheelbarrow by Pte. McLean. At the showgrounds there was a fancy dress football match and joyous dancing of Irish Jigs and Highland Flings that were ‘reminiscent of the old days’. That night a torchlight procession led to where effigies of Hitler and Mussolini were burned, at the place where an effigy of the Kaiser had burned 27 years before. Next day there were more church services and another more-organised procession in which M. Urquhart and E. Symonds, dressed as Chinese maidens, rode in Ye Toy’s cart.

When the peace celebrations ended, a sadness was left. Sixteen Barcaldine men had been lost and twelve more were prisoners of war. As the town waited and prayed for the its youth to return, an honour board was displayed in the Shire Hall gardens.

News stories about the war

Several hundred men of an American Army Engineering Corp were camped at the showgrounds. Newspapers did not mention troop movements but older residents remembered that the Americans were mostly Negroes (as named in news of the day), sent to build an emergency aerodrome which did not prove necessary as the tide of war turned. They remembered that an American plane crash-landed on the old airstrip north of the town and had to be extensively repaired. Council minutes record full co-operation promised to Pilot Officer Trent and his party of the American Air Corp in April 1942.

Fifty girls from Rockhampton Range College arrived on 4 February, 1942 in the charge of Sr. M. John, assisted by Sr. M. Felicitas and Sr. M. Marcella. Superior of the local convent, Sr. M. Josephine, took ten primary students into her boarding house, 18 senior girls were accommodated in a private home, vacated by Mr. and Mrs. William Arthur, and 22 others occupied the presbytery from which Rev. M. Pyke and Rev. T. Page moved into the disused Glencoe Hospital. The students spent a full year at Barcaldine, and all the senior and junior candidates achieved passes in public examinations at the end of 1942.

Over 100 girls from St Faith’s of Yeppoon, run by Anglican sisters of the Sacred Advent, occupied the old St. Peter’s School. Though crowded, the accommodation was adequate and St Faith’s stayed three years in the west until the end of 1944.

Sister Bernadine, who was in charge, stated in her 1943 speech day address that the school would be happy to remain ‘indefinitely’. Sr. Bernadine was assisted by Sr. Helen and a young staff to ensure that all the public examination candidates achieved passes at the end of 1942.

Anzac Day ceremonies at Memorial Clock 1920s, 1930s and 1940s