Anthropologist Norman Tindale identified Barcaldine and the surrounding country as the traditional land of the Iningai people. Their territory includes west of the dividing range to Longreach; south along the Alice River, north to Aramac and Muttaburra. The Iningai were one of the largest Aboriginal tribes in the central west and were said to be a very tall people, some well over six feet tall.

Working Map of Indigenous Languages (SLQ)

Source: Suzanne Thompson, 2017

I acknowledge the people who are the traditional and historic custodians of the land, and pay respect to Elders, past and present, and extend that respect to our ancestors. I acknowledge the water ways, ceremonies, plants and customs of these traditional lands.

Iningai (QLD)

West of Dividing Range to Forsyth Range, Maneroo Creek and Longreach; South along Alice River tributaries to about Mexico; North to Muttaburra, Cornish Creek, Tower Hil, Bowen Downs, and North Oakvale; at Aramac.

Their well-wooded country has broad meandering streams flowing generally west; a few plateau remnants exist. Some people moved southeast to Alpha in later years; The Wadjabangai may be a subtribe.

Alternative Names: Muttaburra (horde name, now a township Muttaburra, Moothaburra, Mootaburra, Tateburra (horde north of Cornish Creek), Teereburra (horde on Alice River) Kana.

Wadjabangai (QLD)

South of Glenbower (now called Lancevale); At Maryvale; south to Blackall; Boundaries fixed principally by exclusion from territories of neighbouring tribes.

Their territory is well wooded with broad sandy plains and meandering streams flowing from the higher country to the northeast. They also called themselves (Kari: mari) which means ‘Salt men’ (Mari=man). Their vocabulary is rather distinctive.

Kuungkari (QLD)

On Thomson and Cooper (Barcoo) river west to Jundah; North to Westland and near Longreach; east to Avington, Blackall, and Terrick Terrick; south on the westrn flank of the Grew Range to Cheviot Rsange, Powell Creek, and Welford.

There are large areas of open grass country. Not to be confused with the Kunggari of the Upper Nebine Creek. They did not practice circumcision. There were at least five hoards with names terminating in (Bara) and (Mari), meaning men. The men of Jundah today prefer the pronunciation (Ku;ngka’ri), others use the accepted version; other valid variations are (Kunghari) and Ku;ngka;i.

Koonkerri, Kunggari, Kungeri, Koongerri, Torraburra (horde), Yankibura (horde), Yangeeberra, Mokaburra (horde), Tarawall (name given to eastern dialect).

What we can learn from news reports

Deaths of Aborigines or reports of their welfare were seldom mentioned in the newspaper. A group camped near Lake Dolly and earned a few rations by cutting wood and doing odd jobs. Most were addicted to alcohol and opium. The Chinese sold them the dregs from their opium pipes, a ‘charcoal’ which caused lethargy, chronic constipation and sow death.

A government issues of blankets was made each May at the Court House but the number of blankets seldom matched the number claimed, a problem solved by cutting them in half. A. Meston, Protector of Aborigines said the natives were nomads and it was impossible to know how many would turn up at any particular station. There was only one sure factor – the number decreased year by year.

In February 1896 a letter to the press, signed by Veritas, called attention to the effect of opium among Barcaldine blacks, predicting that it would wipe them out. An unsigned reply stated baldly the beggars won’t work without opium.

The Aboriginal and Sale of Opium Act of 1897 attempted to stop the practice. Prosecution of Chinese was stepped up. Yen Hop, proprietor of the Rip and Tear gambling den and Young Gee of Ash Street were each fined £7.10.0 in February 1898 and Adam Tee was fined £12.12.0 in October. There were other convictions but it was too late to save the chronically addicted and work permits were resisted because Aborigines feared ‘pieces of paper’ which might lead to gaol sentences.

Natives were sometimes treated at the hospital but its financial problems did not allow for much charity.

The Aborigines who remained in their natural life style were forced away from water holes by dying stock and joined the camp near Lake Dolly. Blanket issue of 1902 found numbers up. There were 37 adults and 7 picaninnies to share 18 pairs of blankets. The very old were given a pair, others one each as far as the bundle went. In the freezing winter of 1902, starving and ill, they were all miserable. A. Meston, Protector of Aborigines, toured the central west from Longreach to the coast in July and removed 52 natives to a mission at Durundar. He also sent some half-caste girls into the care of a protectoress in Brisbane. Lives were saved at the expense of family separation, but there was no happy solution to the Aboriginal problem.

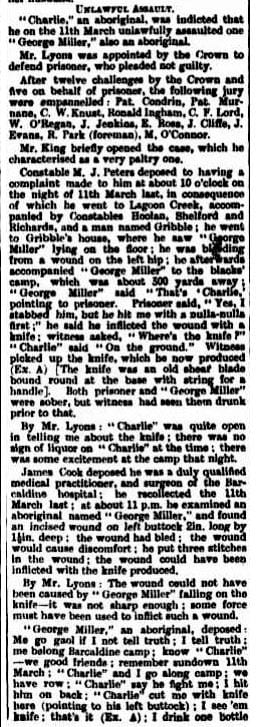

The Case of 'Charlie'

Example of case against 'Charlie' Thompson

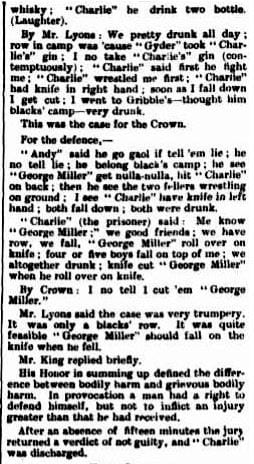

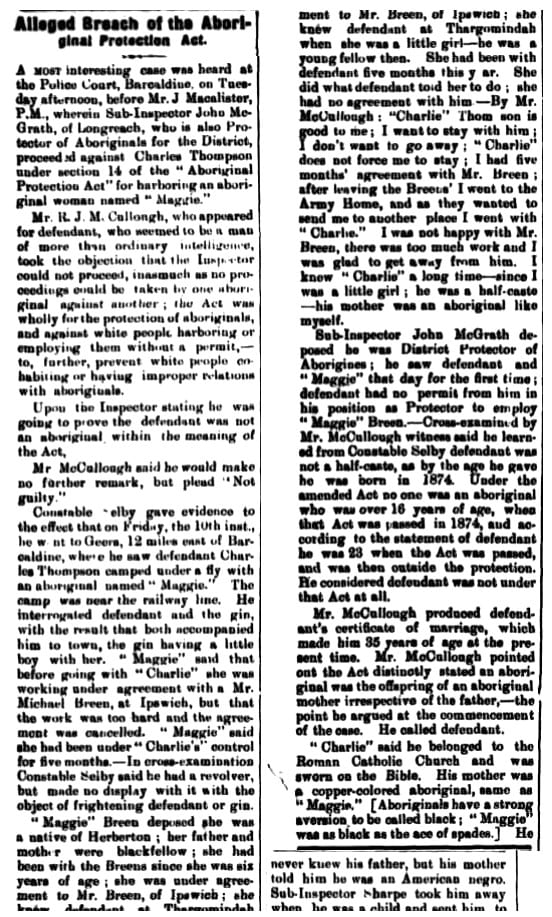

Alleged breach of the Aboriginal Protection Act

In October 1900 a public corroboree at the recreation ground raised about £10 for the hospital but a satirical report in the Western Champion described the music as a monotonous dirge, enlivened only by a keenly exciting dog fight.

It was rare to find compassionate comment on ‘the natives’ but in January 1901 the paper noted:

a strange omission in connection with recent celebrations of the birth of the Australian Commonwealth was that no one thought of giving anything to the remaining representatives of the original and rightful owners of this rich and glorious continent. Not even a sixpence or a blanket or a plug of tobacco was distributed.

In the 1980s the town played an active part in assistance to Aborigines. Beryl and Roy Thompson, with funding through the Commonwealth Aboriginal Development Commission, settled about 18 people in four houses. As home/school consultant, Jenny Thompson was involved with training of disadvantaged people under a Participation and Equity Scheme by which courses in basic living skills were arranged with local tutors at the State School.

You can find more information in the State Library Queensland about the Iningai people in the Longreach and Central West area.

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) has compiled a Selected bibliography of the Iningai / Yiningay language and people held in the AIATSIS Library.

Text sources include Hoch, Isabel. 2008. Pages 14, 15, 40, 91, 125, 149