Teamsters were among the first to make their way out to the west after Mitchell explored the area in the 1840s. The land was surveyed into consolidated holdings, with managers and owners, the rural gentry with staffs of worker. Carriers and coachmen ploughed the dusty tracks even before the railway made its way to Barcaldine. The ‘roads’ were initially made by the teamsters’ travels through the bush, creating tracks for transport and travel. Later the tracks linked the railway to the pastoral areas they served. The routes, lonely and hazardous but dotted with makeshift hotels and sly grog shops, grew shorter as the line advanced. The impact of the railway was gradual over the years, but eventually it spelled the end of the carriers’ livelihoods.

In the mid-1880s, the demand for carriers was high with the healthy state of the wool market. Combined with the introduction of capital into the Barcoo district, improvements were made in all directions out from the line. The large runs were being systematically stocked and worked, and carriers were in great demand.

Their rates for carrying varied along the line. Sometimes it was from £10 to £12 per ton as obtained at the Comet, and sometimes as much as £30 per ton. There is mention of £300 being refused for a team of bullocks with waggon and tackling, so when times were good, the carriers had a good livelihood.

The Great Western Carrying Company started in opposition to Wright, Heaton, and Co., and they induced a large number of teams to come from the southern colonies, and from the Northern and Southern and Western lines. The number of strangers arriving within a month was estimated at from 300 to 500 teams.

After the line crossed the Great Dividing Range and the work was ‘on the flat’, a serious crash came. There being no difficult range to cross, and the distance for delivery of loading comparatively short, quick trips were made, and the storage sheds soon became emptied, and the drought arrived curtailing the suspension of improvements on the stations; no more material was needed.

Many of the carriers hurried away again; but others remained hoping for a break in the drought, and a return to ‘the good days’. But it never came. The railway receipts soon declined, prompting the Government to speed up the line’s advance to the good country in the west. But the drought meant that for a time carriers had nothing to do.

Although rates were high, a journey west was risky; carriers had to carry their own feed, and often take a water cart with them, and could lose half their team on a trip.

By the time Barcaldine was reached by the rail line, there were about 12 to 20 carriers operating in the area.

In May, 1887, Barcaldine numbered about 2000 people, but a very large number had nothing to do. The carriers, owing to the short distances to travel, found their occupation practically gone. Fortunately, the Croydon broke out, and many teams moved on to take advantage of the new area opening up.

The north side of the line in Barcaldine was devoted to the railway department and a large carriers’ camp. It became the place where the carriers waited for loading. For three years it remained the Terminus and the working class population mushroomed. (Hoch, 2008, p.12)

Teamsters/carriers in western Queensland

‘Teamsters or carriers as they were sometimes known, provided an essential service of carrying goods and stock across trackless country to the new stations of western Queensland. The first teamsters into a new country were limited to the use of drays, which were more manoeuvrable than wagons. Among the essential equipment of these first teamsters were axes to clear tracks of land, picks and shovels to make creek crossings and a piece of brightly coloured rag. The rag was tied to a wheel so that its revolutions could be easily counted. These rough measurements of distance gave carriers a guide for cartage charges and provided a bush standard which remained in use until the introduction of surveyors and roadmakers’. Source

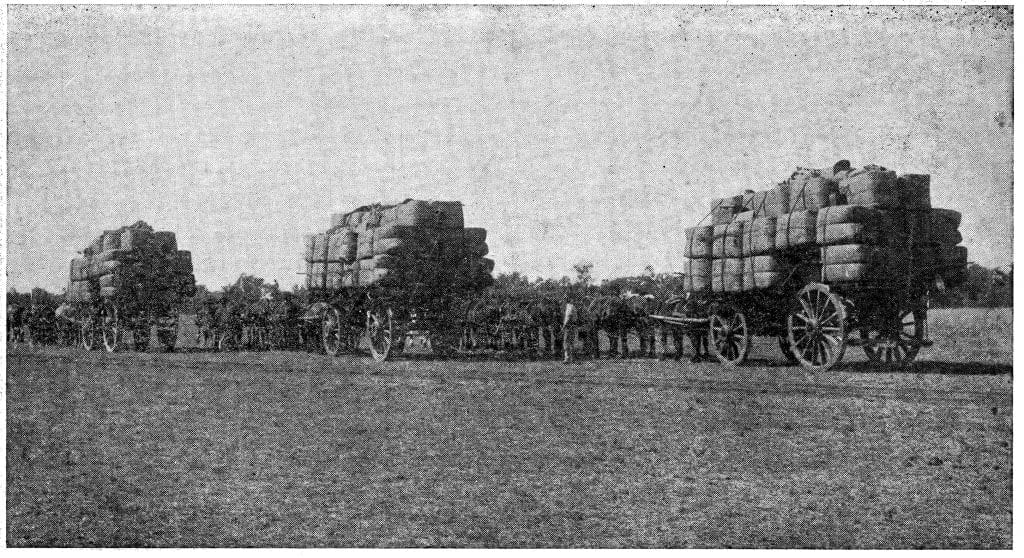

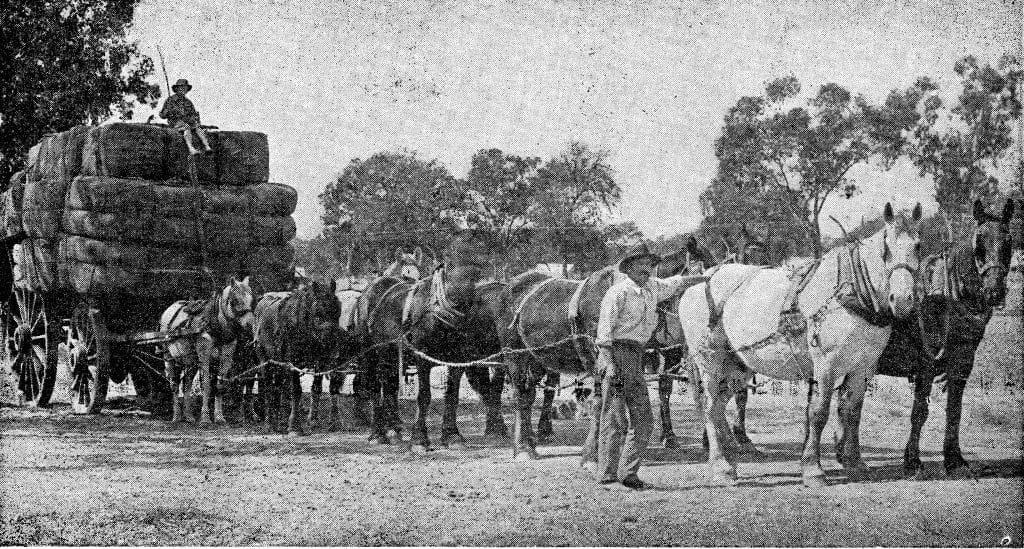

In the early days, it was found that the horse and bullock drays were unsuitable for transporting wool and supplies from and to the stations and towns. Four wheel wagons were introduced, but in the beginning they were fitted with narrow wheels. These were very hard to pull when the ground was either dry or very wet. Later, these wheels were fitted with 11 inch tyres and the wagons could carry more than 80 bales of wool or a load of 14 tons. These large wagons were often drawn by twenty- eight horses yoked four abreast, and in wet weather, it was quite usual for teams to be doubled or trebled to pull the heavy loads out of boggy country. It was understood that the limit was about fifty-six horses. Any more hooked to a wagon could seriously damage or break the draw rods.

Carriers took great pride in their teams; many of the leaders wore dress harness covered with horse brasses, brass ornaments which are very popular now for house decorations. Usually their wives and families travelled along with their husbands in a covered wagonette. This was done, one of the carrier’s wives told me, so that the wife could look after the money, as there was a shanty about every twenty miles along the road to entice the thirsty carriers to part with their cheques. The wives who lived in one of the towns would often find to their sorrow that there was little of the cheque left when the teams came through. Source

About 1914, motor lorries appeared on the roads. These so-called roads were still only tracks beaten hard by the hoofs of thousands of horse and bullock teams, but possible at least for more progressive transport. These lorries had solid tyres and the teamsters saw in them a great threat to their living. They did everything in their power to prevent the lorries getting through to their destination. They criss-crossed the road in boggy patches. They plugged the pipes beneath the roads at bore drain sections, so that the bore water would flood the road, and they tried every trick to drive the lorries off the roads. However, as the lorries did not use grass or water, they were popular with the station owners who saw their first chance of receiving perishable goods in good order with these lorries, which could travel fairly fast by day and by night source

By the 1920s in Barcaldine, motor lorry carriers were beginning to take over road transport. Steve Lennon, for example, advertised the service of a 1 ton truck with seats for passengers and claimed he was willing ‘to have a crack at anything’.