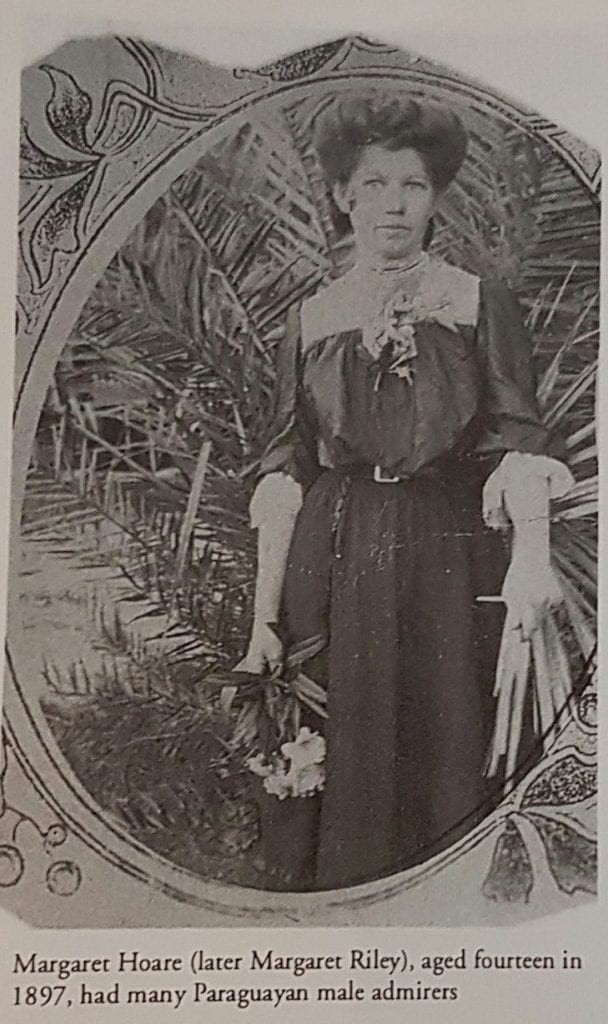

Margaret Hoare was nearly 11 years old when her father decided to take the whole family to Paraguay as part of William Lane’s ‘New Australia’ party.

Born on 22 January 1883 in Bogantungan, a staging post along her father’s carting route, Margaret Riley died in 1989 at the age of 106. She was the third of 10 children of the carrier Denis and Mary (nee Sammon) Hoare.

Margaret related her story to Anne Whitehead in 1988. It was published in ‘Paradise Mislaid: In Search of the Australian Tribe of Paraguay’ in 1997.

Her father made the decision to leave Barcaldine and head to Paraguay in 1893.

“He was out of work, and then he heard of this blooming Paraguay business … I think it was through the Worker that he heard about it. He said William Lane was forming a settlement in Paraguay and he was thinking of going there. My mother didn’t want to go, she wasn’t keen at all. Anyway, of course, what he said was law, but she said, ‘I don’t think it’ll work’. He said, ‘Oh it’ll work all right because there’s a lot of people going and I’d like to go’.

Every adult was supposed to put in £60. He sold the house we had on an acre of ground, a good big piece of ground in a good position. He sold his teams, his draught horses and his saddle horses and he wagons, and he must’ve had a bit of money and whether he put it all in or not, I don’t know. They said you had to put in whatever money you had. But I know my mother had a few sovereigns and she kept them. She said she wasn’t going to put them in because she didn’t know how it was going to work out and she might want them. And she did, later on.

It must’ve been a big decision for him to make because there were seven of us and my mother had a young baby. But he said, ‘Oh well, you can give it a chance’.”

Denis sold the house in Barcaldine and they all went firstly to Sydney by train, and then onto Adelaide to catch the Royal Tar, being the second contingent of travellers to seek the life in ‘New Australia’ in Paraguay.

“When we went down to Sydney, they weren’t sure whether they could take the women and children so the men all went to Adelaide and we were all left behind. We had Christmas in Sydney. But any way then they [Lane had wanted the men to go and be followed six months later by the families] decided there was room for the women and children after all, and we had to go by train from Sydney to Adelaide. At Albury my mother saw they were taking our big grey box off – my father had packed everything that wasn’t wanted for the trip into that box, her hand sewing machine, blankets, sheets and pillow slips – and we had to change trains. We were all roused up, some of us couldn’t find our boots and some couldn’t find their hats. Oh, such a fuss there was to get out of the train in time! We got onto another train and at last got to Adelaide and then we were shunted off down to the wharf”.

Margaret, nearing her eleventh birthday, remembered loading and boarding the Royal Tar. The ship left on 31 December 1893 from Adelaide.

“The Royal Tar was out at sea and we had to load into small rowing boards to go out to the ship. Oh, it was such a scruffle! So many women and so many youngsters and they were throwing the kids up to the men on the ship and they’d just manage to catch them. It was really funny! My father was there and I can remember him catching me and putting me on the deck, and saying, ‘Now you just stop there!'”

The Hoare family, with seven children, were allocated a curtained cubicle below deck. As soon as the ship was under way, Margaret became violently seasick. Her mother suffered even more, and couldn’t look after Dan, who was cared for by a nurse and brought to her at feeding time. Margaret soon recovered and found her sea-legs, helping with the other four children.

This second batch of colonists arrived by riverboat in Asuncion in March 1894 and were met be a few of the earlier seceders. Only one man, William Kempson, a shearer from Barcaldine, was sufficiently unnerved by the horror stories to head straight back to Australia. The others including the Hoare family and young Margaret made the train and carreta journey out to the colony.

“We arrived at the main settlement of New Australia some time in March, I think. They had built a few houses there with thatched walls and thatched roofs, but there wasn’t a house big enough to accommodate a man and wife and seven children, so we lived in a tent for a few months. It seemed to be a very wild country. The settlement was on a plain, just outside a big monte.”

A new settlement, Loma Rugua – Hill End, was established 20 miles to the south. Fifty single men and ten families of the second batch, including the Hoares, moved there.

“They built us a house, two rooms and a big open breezeway for a dining-living room with mud walls and a thatched roof. The kitchen, with an open fire, was outside, because they had to be very careful with the thatched roofs in case they caught alight. Our outhouse did burn down one day and my father had to build a new one.”

William Lane had taken up temporary residence at Loma Ragua and Margaret remembered him as also retreating to his house, some distance away from the rest of the camp.

‘He wouldn’t join in with the common people. He had a two-bedroomed house with thatched sides and a thatched roof. He’d come into the settlement and say what he wanted to say and do what he wanted to do, and then he’d go back to his cottage. My father said he wouldn’t mix in with the rest of them.”

By 1897, Margaret was fourteen years old, and Mary Hoare was desperate to return to Australia. She had always hated Paraguay, and at last, with so many colonists leaving, Denis Hoare capitulated.

“There was nothing there for him. No work and no money coming in. And they didn’t like the idea of us mixing in and marrying into the natives. I don’t know why my mother felt so strongly about that because they were quite decent people. I felt a bit sorry about it. It was a free and easy life for us, and it wouldn’t have been such a bad thing. I suppose we would have lived on the country the same as they did. It all depends on who you’d marry.”

Leaving Paraguay

“We came down to the Argentine and my father was going to get a bridge-building job on the Rio Negro but then that fell through. Anyway we all got the measles and had to go into hospital in Buenos Aires, and my youngest brother died there in hospital. After that my father came and got us out of our sick beds because he had heard that a British cargo vessel had come into port and he had decided we’d go to England on that. Well, we were only out at sea a week or so when my eldest brother contracted smallpox. So the captain called in to the port of Santos in Brazil and decided to take him off the ship. He said otherwise the ship would have to be quarantined and he didn’t want that. My father announced that we’d all get off. But there was very bad yellow fever in Brazil at that time and the captain said it wouldn’t be wise. In the end my brother was left in the hospital in Santos, in the care of the British consul. We waited six months in England for him, but he didn’t turn up until long after we were back in Australia.”

Return to Barcaldine

Returning to the flat sheep plains of Barcaldine was a difficult readjustment for Denis Hoare.

“It wasn’t easy to come back to the place he had left. He found it hard to get work – because he was an older man, of course, and he wasn’t trained to do anything much. He was a handy man but he had to take any job he could get.”

In 1907 public baths were opened in Barcaldine, and the first caretaker – who kept his position until he retirement – was Denis Hoare.

The children just had to settle back into life again too.

“We went to school for a while and then we got jobs. We weren’t trained for anything and we got domestic work. We had to do the best we could”.

Margaret married a policeman, Edwin Riley, a World War I veteran who had returned wounded from France. They had three children – Bill, Edna and Edwin always known as Mick. During WWII, Mick was one of the crew of HMAS Sydney who lost their lives when the ship was sunk.

Margaret said the trip to Paraguay was the best time in her life, and her father’s life too, although her mother was never persuaded to like it.

In Brisbane, I recently met some of the descendants of Denis and Mary Hoare. My cousin, Louise Duffy, married Brendan Sammon. Louise is the daughter of Terry and Patty (nee Farrelly) of Barcaldine.

Find Out More about the Colony in Paraguay – a facebook group is collecting information about the colony, its inhabitants and descendants (living in Australia and in Paraguay).

The Legacy of 'New Australia' in popular culture

The title track to the 1980 Redgum album Virgin Ground is also about the New Australia Colony.

The Melbourne-based Australian Folk Punk band The Currency have a song called “Paraguay” which tells the story of New Australia.

The Weddings Parties Anything song “Drifted Away” is also about the New Australia experiment.

Graeme Connors, Australian country singer-songwriter, wrote a song called “Boomerang in Paradise“, a nostalgic, sympathetic retelling of William Lane and the New Australia colonists.